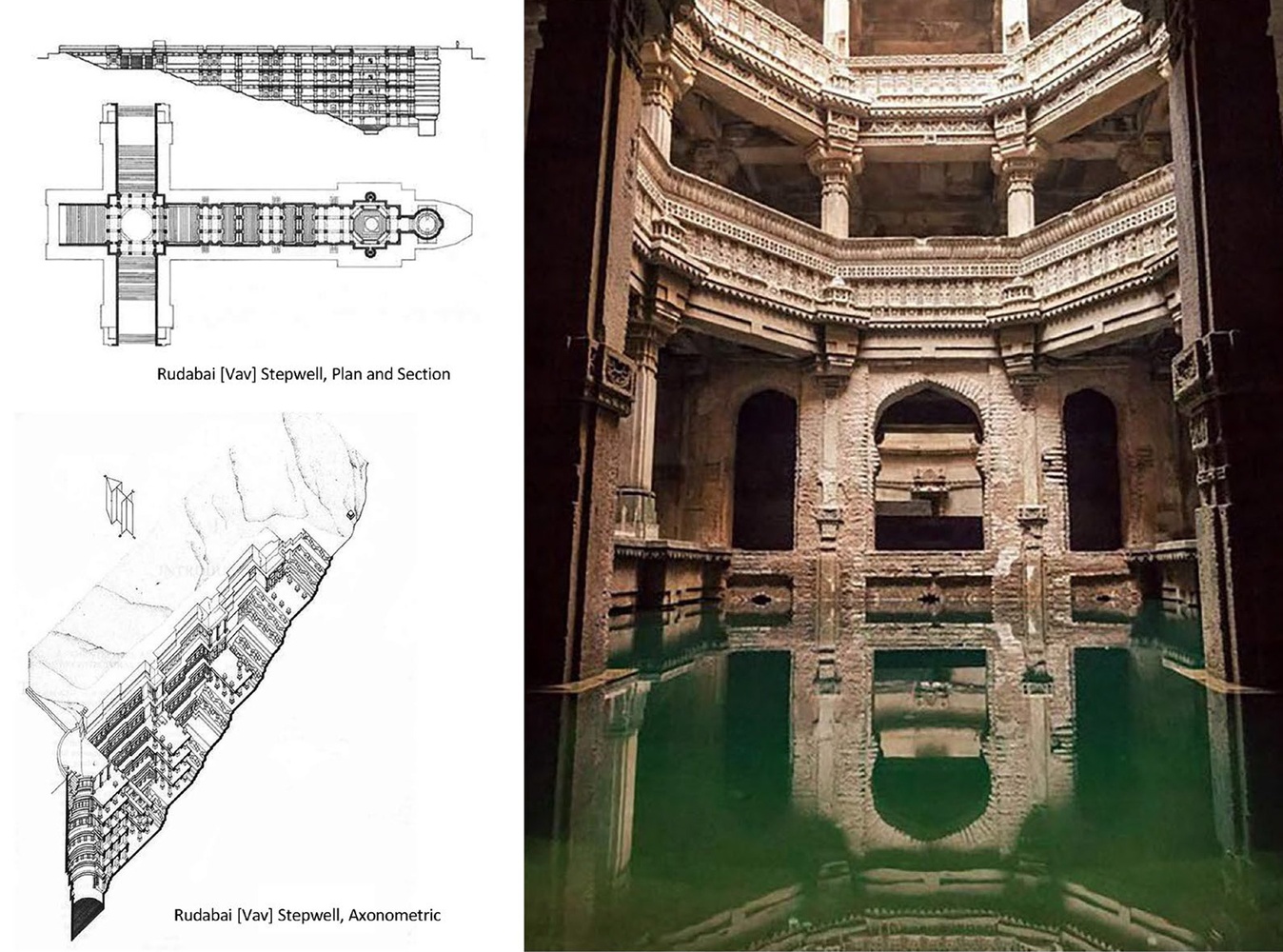

The RudabaiStepwell close to Ahmedabad was built by a princess, its Vav-Type in support of women, creating a social space to socialize while fetching water from the aquifer.

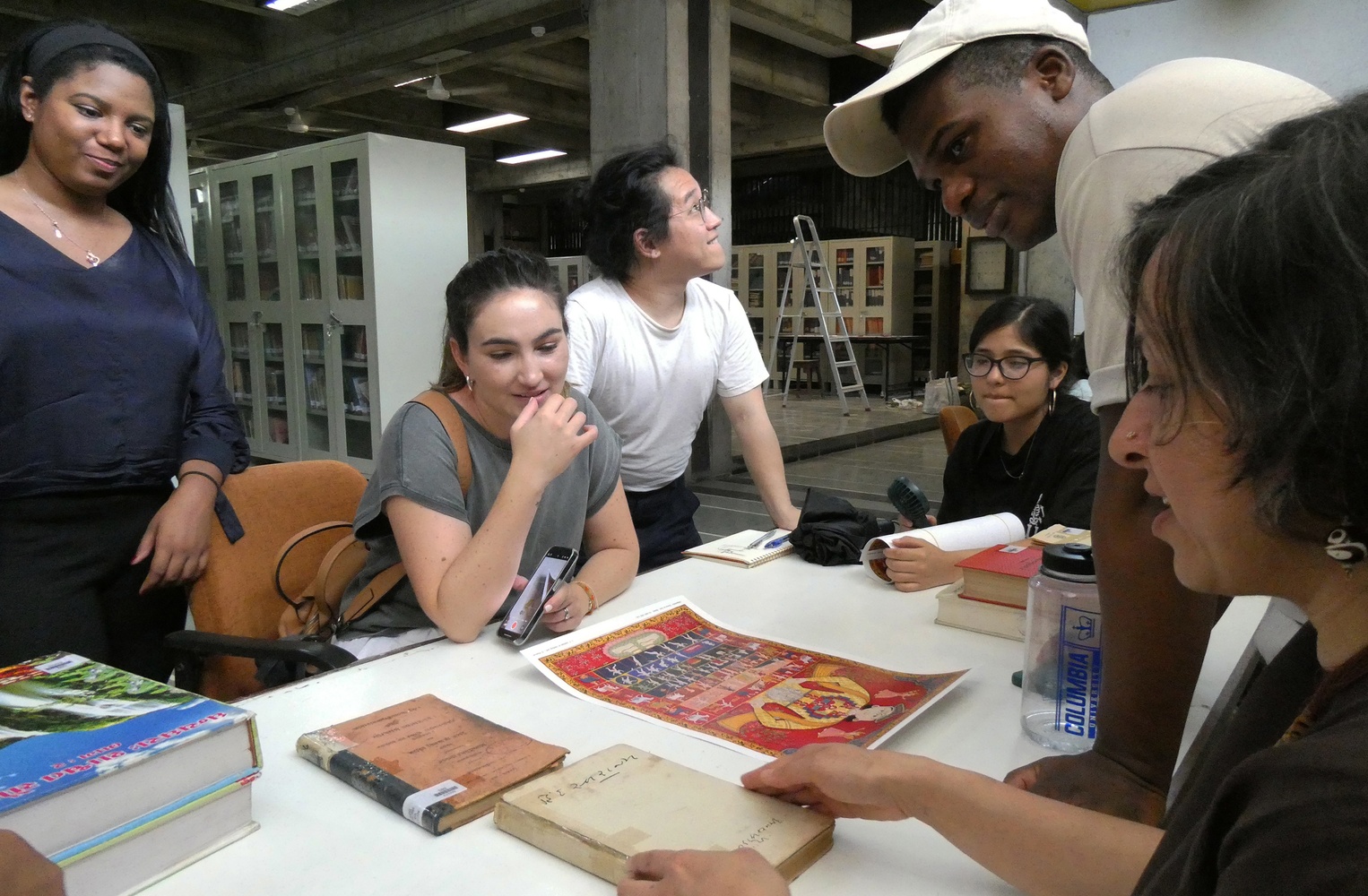

Drawings by Anant National University. Photo by Sonal Beri.

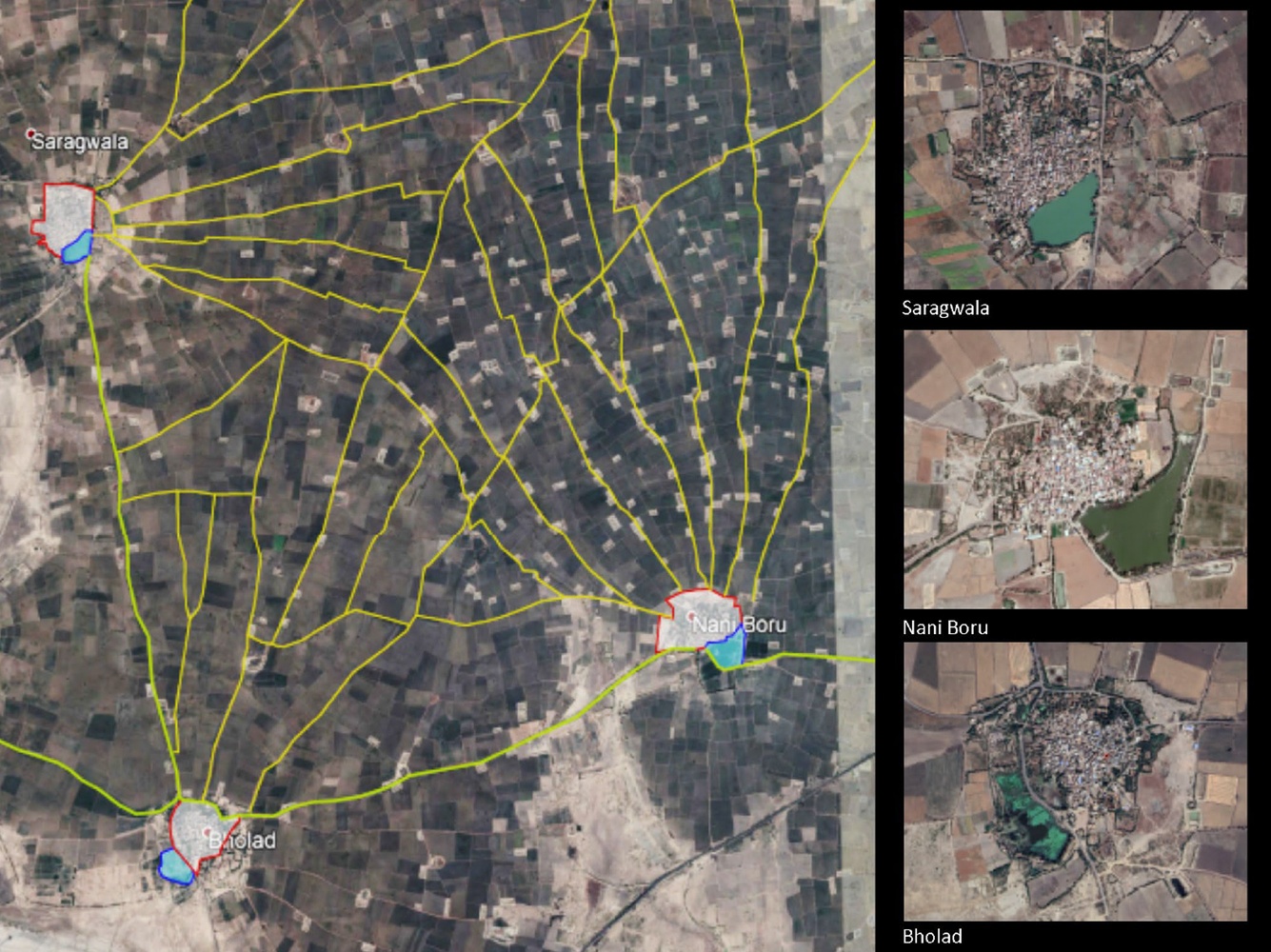

Typical Gujarat’s pattern of cultivations with three villages and their relative Talavs, connecting network of irrigation lines, and secondary ponds to control monsoon water.

Images from Google Earth.

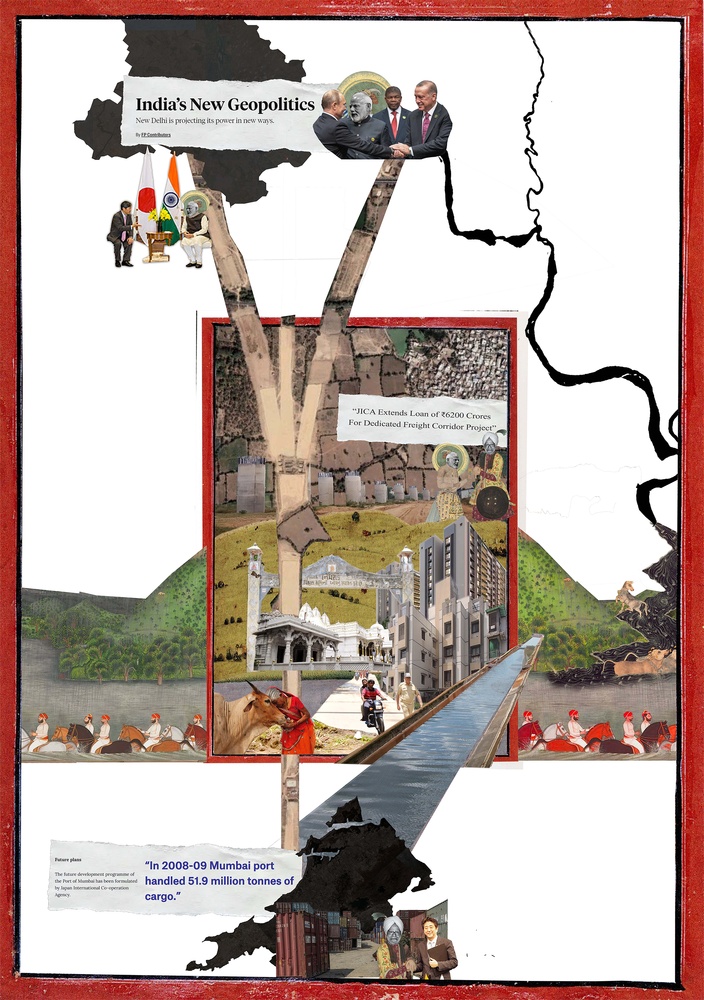

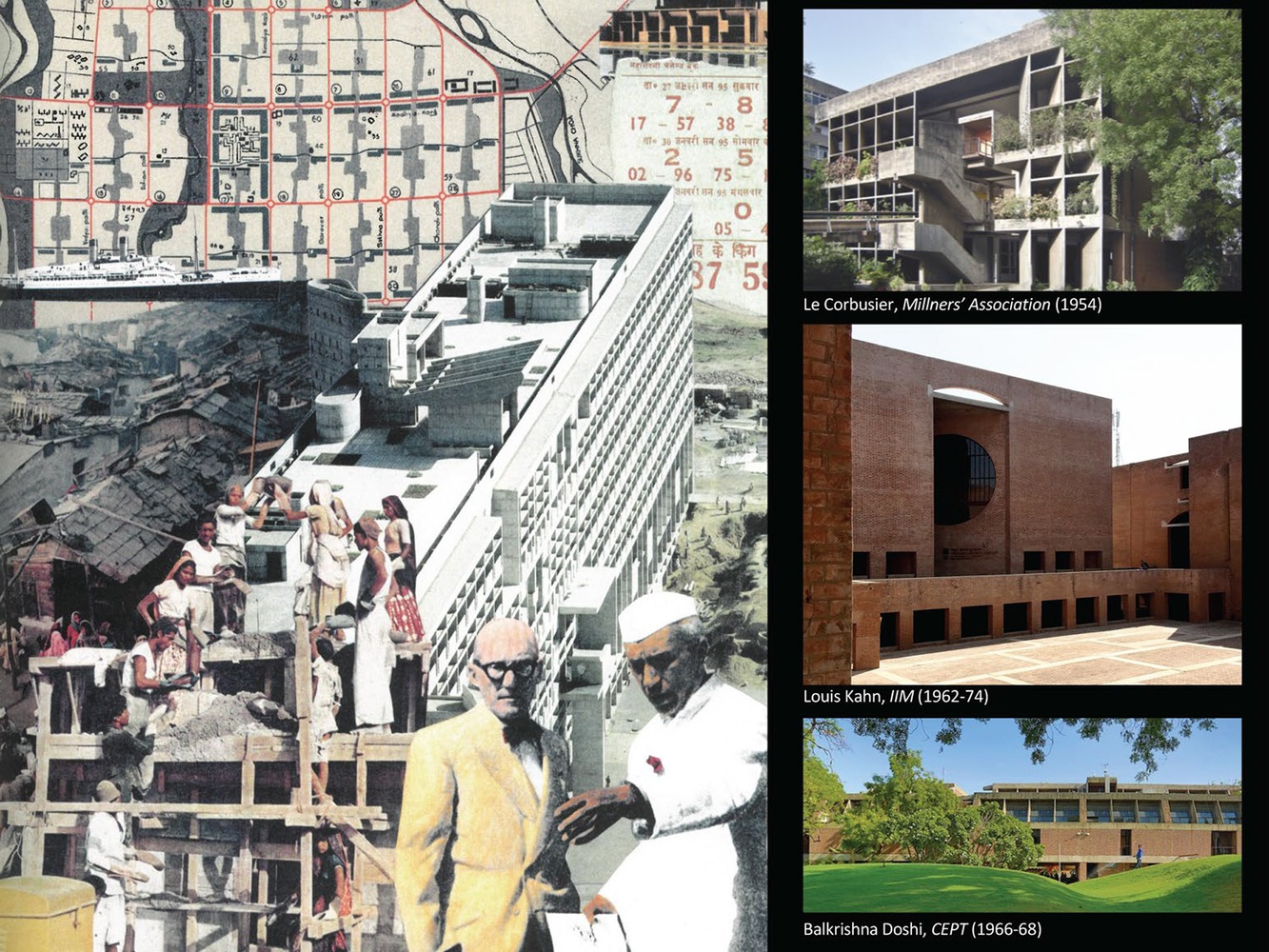

Left: David Wild, Collage: LC, Nehru, Chandigarh (1982);

Right: Three examples of Architecture Masterworks in Ahmedabad that we will visit.

Left: Collage by David Wild from his book Fragments of Utopia, published by Hyphen Press. Right, from top to bottom: Photo of LC Mill Owners’ by Motaleb Architecten; Photo of Kahn by Sonal Beri; Photo of Doshi provided by Doshi Foundation.

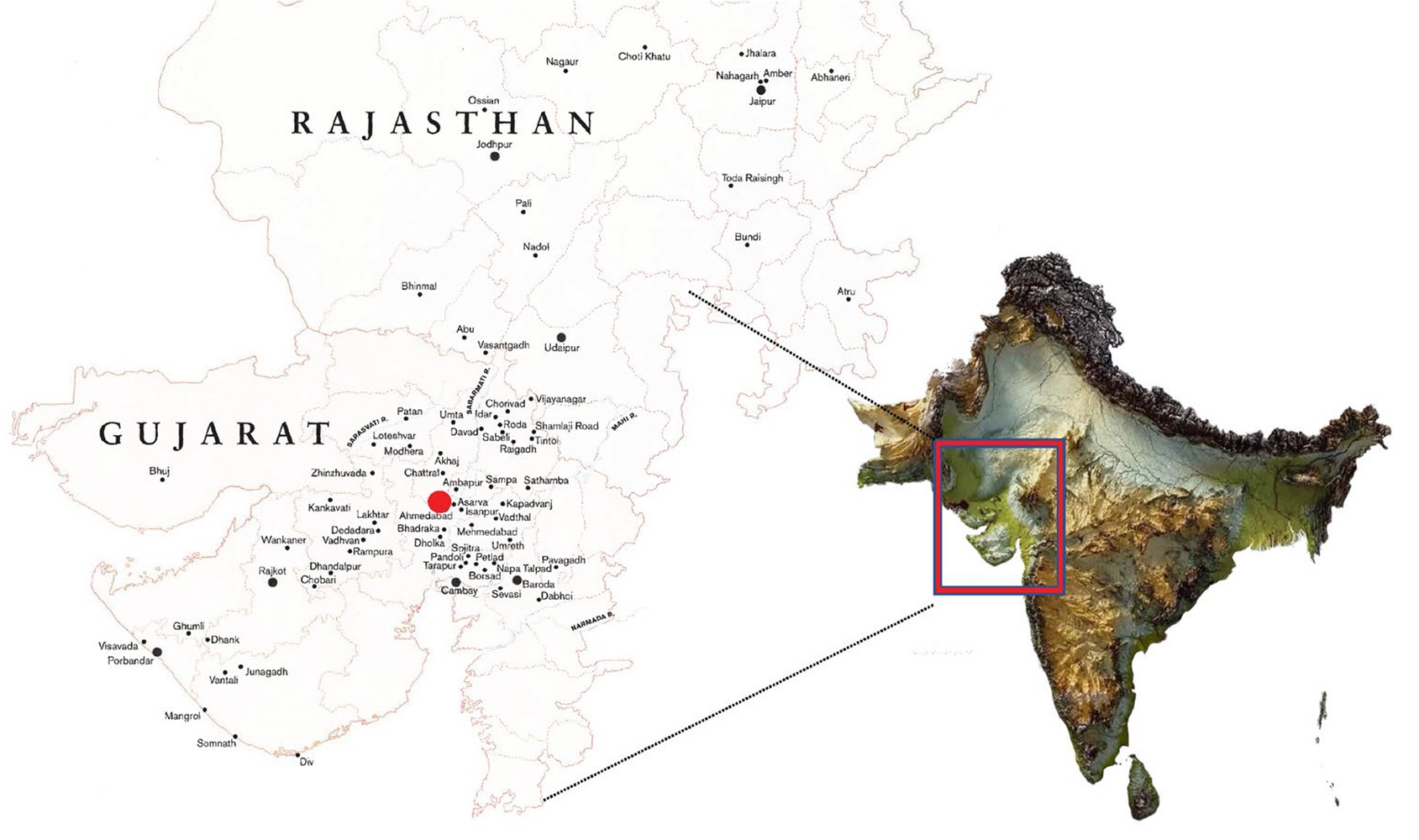

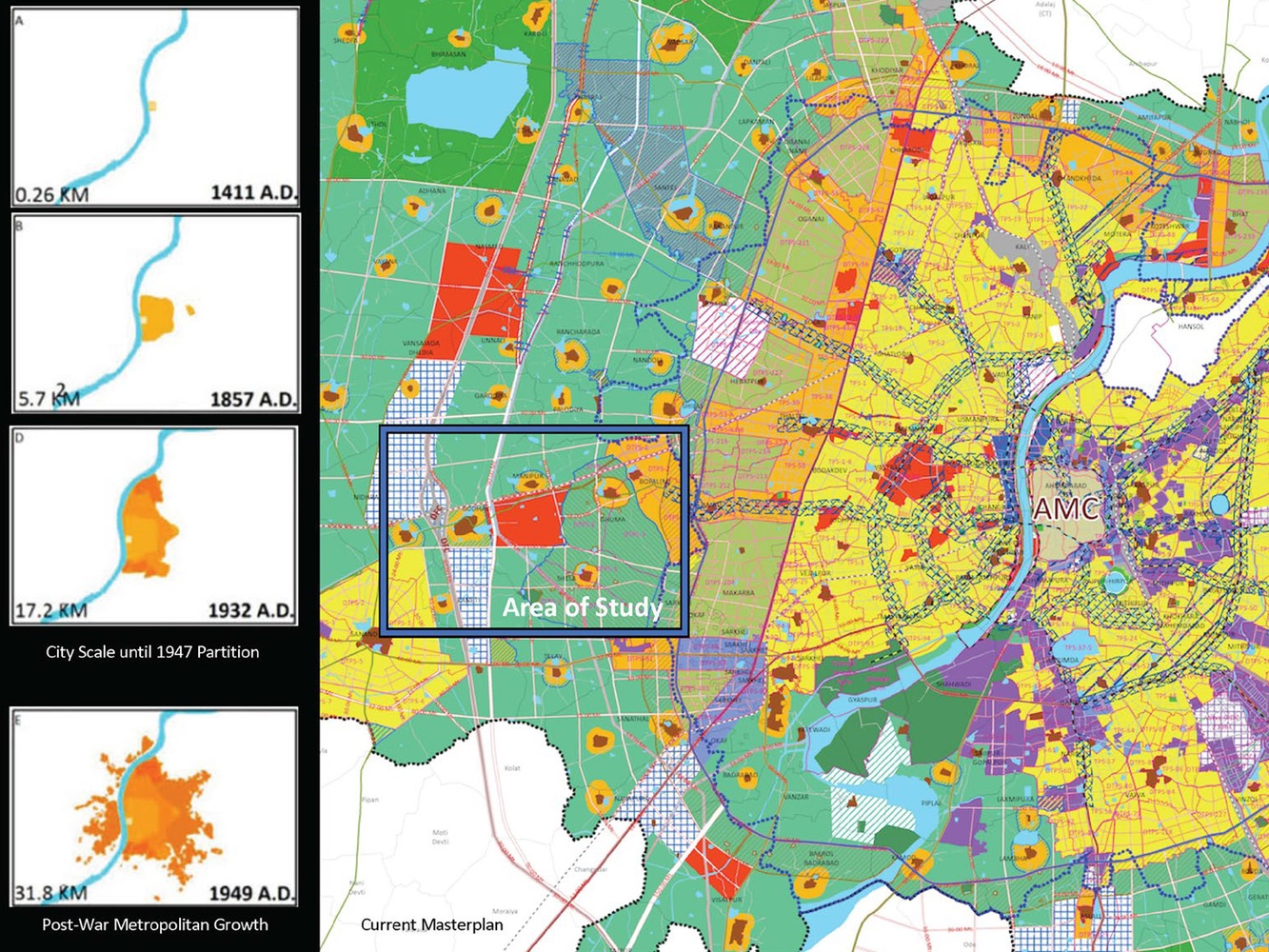

The city of Ahmedabad and its growth to the west fringes is pushing into agricultural land, absorbing historical villages.

Maps provided by the City of Ahmedabad Planning Office.

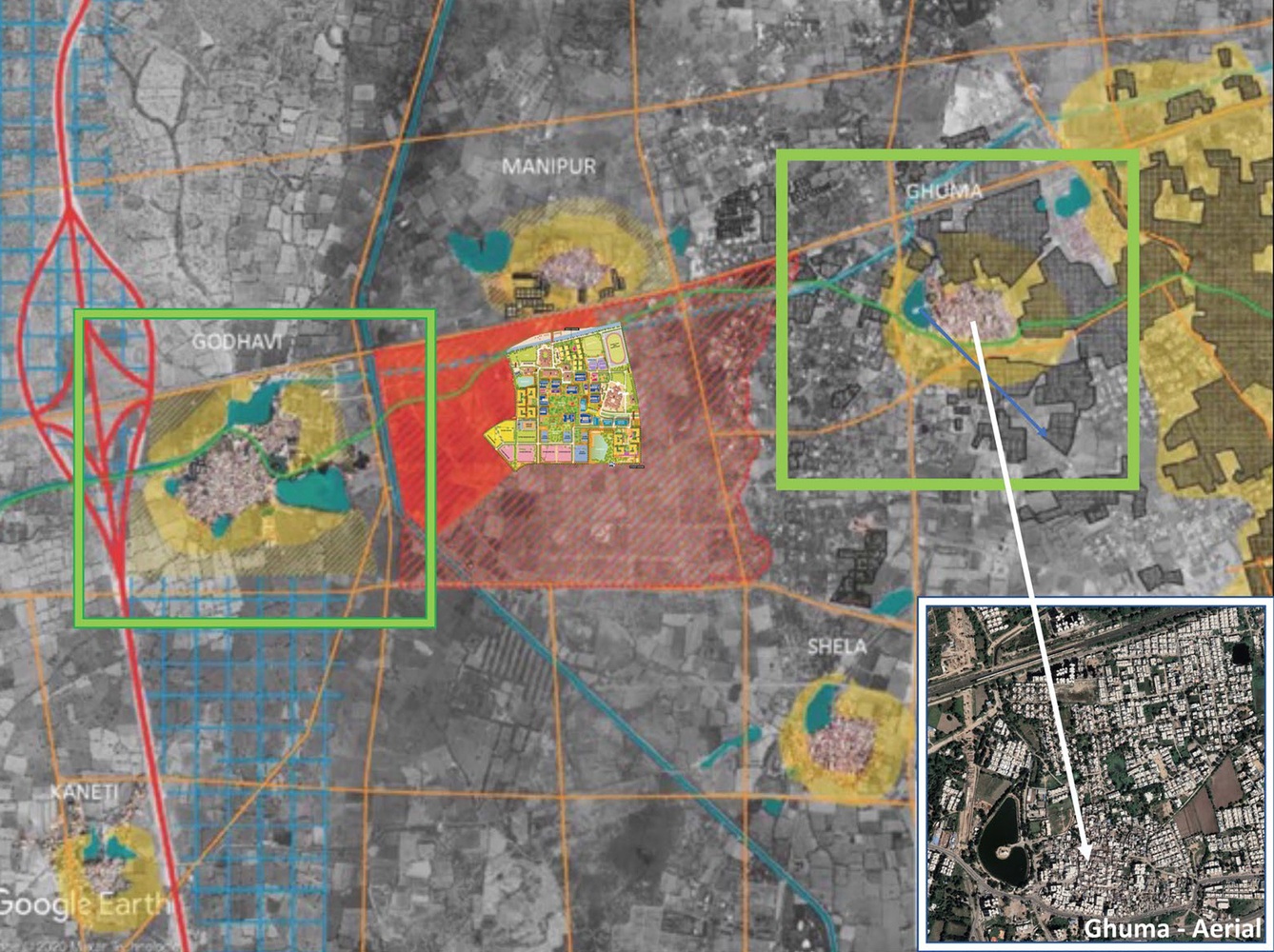

Detail from map of study area: the Village of Ghumahas already been encroached by clusters of new development, while the Village of Godhavilies between a planned “knowledge and institutional zone” and the new Ahmedabad’s ring road under construction.

Aerial view from Google Earth with an inset detail of Anant University Plan provided by our Partner Anant University.

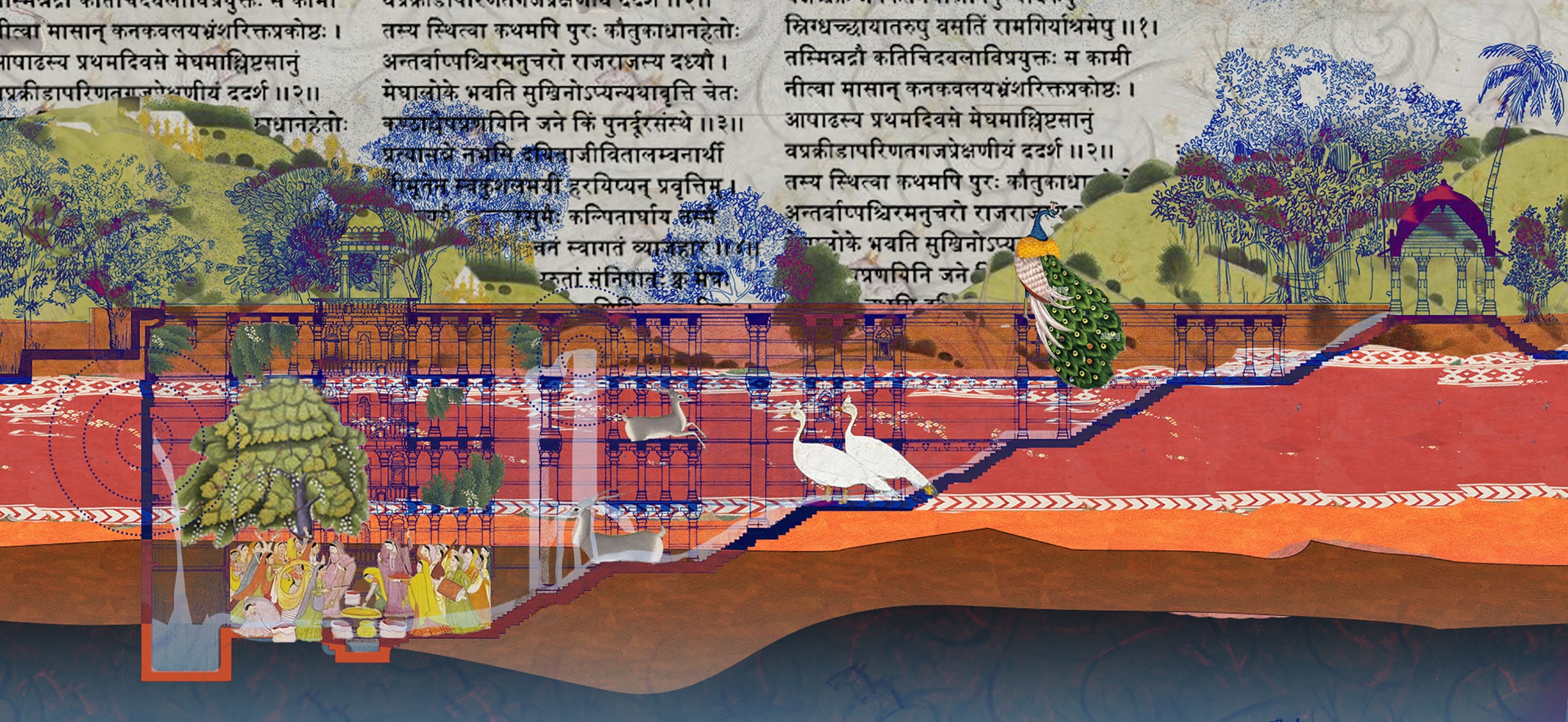

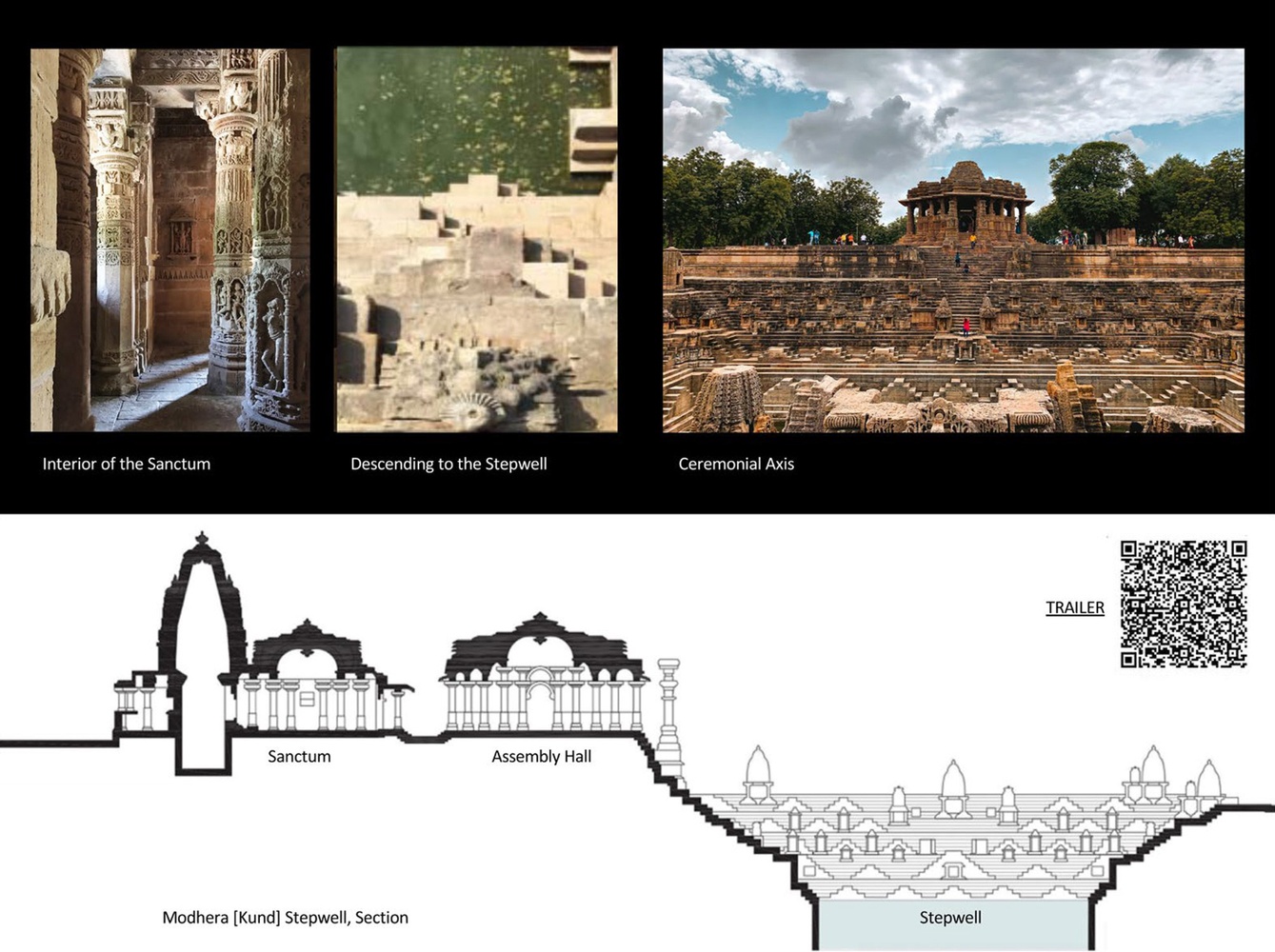

The QR Code on the right side of the section through the ModheraSun Temple and its Kund-type Stepwell (1026 CE), is a short video testing the integration of sketches, documentation, and video footage, to introduce the notion that historical architecture operated as an environmental apparatus.

Section drawing provided by Anant University and all photos by Sonal Beri.