1

Convergences

2

Modalities of Appearance

3

Truth, Politics, Disintegration

4

Queer Worldliness

5

The Process of Breathing

6

Beside and Between

7

Saturation Points

8

In Absentia

9

Reorienting toward Each Other

Under the Museum,

Under the University,

Under the City: the Land.

—Decolonize This Place

We need to imagine what movements, shapes, visions, and possibilities come next; to imagine how institutions and cities might cultivate new forms of relational life, indeterminate political worlds, and contingent modes of living with others. These potentialities are at the heart of this concluding conversation with Amin Husain and Nitasha Dhillon, artists and organizers who work to convey the urgency of abolitionist activities—particularly at a time when exponents of liberalism, desperate to secure a dominant social position, are appealing directly to forms of political violence.

In May 2021, the Museum of Modern Art in New York summoned the New York Police Department to fortify the building and block the entry of hundreds of people who had gathered there to protest the museum trustees’ financial investments in the Israeli army (which was at the time laying siege to Palestinian homes and communities in Gaza and East Jerusalem). Five members of the activist coalition International Imagination of Anti-National Anti-Imperialist Feelings were banned from the museum and one member was arrested.

Dhillon and Husain, who together make up MTL Collective, and are among the principal organizers of the MoMA protests (as well as recent protests at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the American Museum of Natural History), describe these actions as the capitulation of liberal institutions to state violence and its colonial tethers. Museums such as MoMA cannot be understood apart from the greater moral and political framework they were designed to cohere, Dhillon and Husain argue. Thus appeals for institutional change turn into calls for insurgent practice.

Art after Liberalism shares these convictions while making note of their radical distance from the workings of normative aesthetic critique. It invites readers to share them as well, offering a space for critical reflection in the company of others.

Nicholas Gamso (NG)

“Under the Museum, Under the University, Under the City: The Land.” This statement, which has appeared on banners at Decolonize This Place (DTP) protests, is both a rallying cry and an analytic. It calls attention to the ways that liberal institutions decimate communities and erase their histories. What could we say lies buried beneath the concept of the public sphere? Beneath political culture? Is there an intrinsic relation between conceptions of the public and the constitutive violence of the modern nation-state, as Fred Moten suggests when he refers to the “fiction of the general interest”? And what does this mean for the targets of protest and direct action?

Nitasha Dhillon (ND)

The banner—“Under the Museum, Under the University, Under the City”—comes from an understanding that decolonization is not a metaphor. Central to decolonization is water, air, and land, and without them, decolonization is a shell game (this has been written about by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang. And there’s another text by Chandni Desai). Land is central to decolonial practice. What these institutions do, especially when they are tied to Western modernity, is make you think that the museum or the university is a global project—specifically, a global project of thinking—that somehow exists in outer space or is not connected to land. Or if they are in, let’s say, New York, there’s another kind of attraction. The museum and the university are part of the culture of New York. And what is the culture of New York? It’s a capitalist culture, it’s a settler colonial culture. I think what we wanted to do with that banner was really put the centrality of the land back into the conversation. Especially at a moment when there is a lot of interest in decolonization and abolition at the rhetorical level. But it doesn’t connect to things like land, or actually the abolition of places like the prison. Museums are also part of similar nation-state building projects, and so the museum needs to be abolished, too, in order for something else to emerge. Land is a starting point.

Amin Husain (AH)

I think it’s interesting to look at the banner and ask, how is it different from other banners? It’s almost like a label—people that hold the banner are really holding a label. If you see it in front of MoMA, it’s as if it’s saying, look, here, there’s land—act. So it takes it from an intellectual space to a physical place where you can do something. And in that sense, the banner is a call. I think, also, it’s trying to connect to May 68. There’s a lineage: under the cobblestones, the beach! So it’s a way to recognize this moment as having a lot of possibility in it. A lot of harm, but also a lot of possibility.

ND

There was a banner that we had at the fourth anti-Columbus Day tour. It said “public land is equal to stolen land.” We were walking from the American Museum of Natural History through Central Park making all these different stops. The last stop was the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And on the way we encountered Seneca Village, a Black community whose land was taken by the city through eminent domain. With settler colonialism—and we know this is the case not just in the United States, but in many settler states like Israel—public land is basically stolen land. You can see this even in the legacy of Theodore Roosevelt and how national parks are associated with protection or environmentalism. That is what settler colonization does. It separates people from their land. Public interest is more like the interest of nation-states, which are built on colonial violence. And it’s not that countries like, for example, India are any better, right? In India, the public interest is now the interest of the nationalist or Hindutva movement. As things get tied to nationalism, there’s some sense of supremacy. And so the public, in these examples, is definitely something that should be striked as well.

AH

I’m also thinking about the public. Who dictates the public? Who determines it? On what basis? It’s the law that really determines what is public. We’re coming from a place where we know what the law is—the law is a byproduct of power relations that maintain the status quo. So an appeal to power as a strategic option isn’t effective. So why would we even hold on to this idea of the public? The plaza at MoMA is quasi-public, meaning it is privately-owned public space. This was an agreement made in exchange for leniency around rezoning. Paramount, across from MoMA where the post-MoMA future took form and shape, promised to hold and maintain a public park—but these public parks can be shut down at any moment. And they have been. So thinking about the public as a tool of repression is important.

I also think is worth saying that phrases like “under the museum” and “under the university” encapsulate the idea that we need to be talking to each other in our actions. In a way, the resistance—or the things that we do against something—is a byproduct of our main goal, which is to have a conversation with each other that isn’t mediated by them. The conversation is that under these institutions, there is land. Why the university and why the museum? Because the longevity of the nation-state project is predicated on these two institutions doing their job. With the prison it’s actually clearer—what it’s doing is eliminating people—but we’re more interested in soft power.

NG

Both DTP and MTL Collective have foregrounded museums and liberal institutions, but your work is not limited to these sites. I’m actually thinking about the actions you organized last summer in the Bronx in response to NYPD violence around the city. As I understand it, this was not actually framed as an art action. So I find myself wondering about the need to, as you put it, de-exceptionalize institutions and to re-scale arts activism in a way that accounts for other kinds of state violence, racial capitalism, so on. How might these actions help us to revise our perception of art and culture as fields of political engagement? How do we connect or how are institutions connected? How do we realize the connection between Palestine and MoMA and the Whitney?

AH

If you are referring to the actions like FTP (Fuck the Police), which organized around the subways and the police, it’s all part of a larger formation. DTP has been asked by a lot of community groups to utilize the platform and the analysis and to fuse it with radical thinking and action, which treats the city like the museum—in a way, they are the same. We’re into mapping and counter-mapping, experimenting and testing, as a way of learning and as a way of figuring out how to move more effectively and what the next steps should be.

I think it is important to recognize that everything we do, in some ways, is training. It’s about developing a vocabulary of liberation and difference—to recognize difference is not a bad thing—and to ask what solidarity looks like as a way to build power and to get free over time. The other aspect of shifting from the museum to the city is that people start to see similarities and differences and to learn how to move together in these different contexts. The street is very different from the lobby, although perhaps there is less difference when it comes to MoMA. The stakes here aren’t about who gets included in MoMA, who gets excluded, or whether we get rid of Leon Black. We’re done with being included and excluded, and instead trying to have an argument about the parameters of inclusion and exclusion. The whole point is who’s in control of what and to what end?

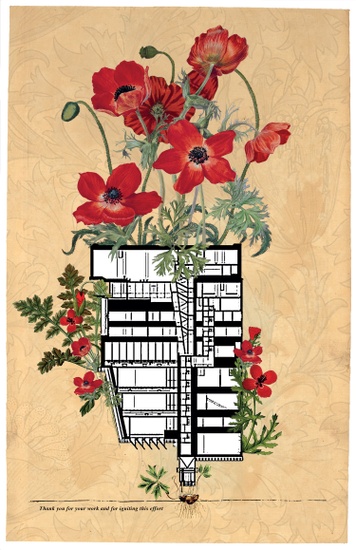

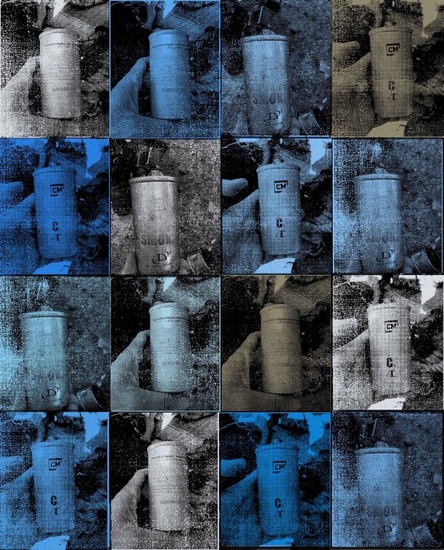

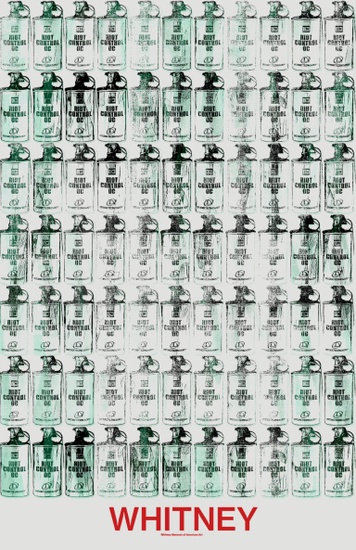

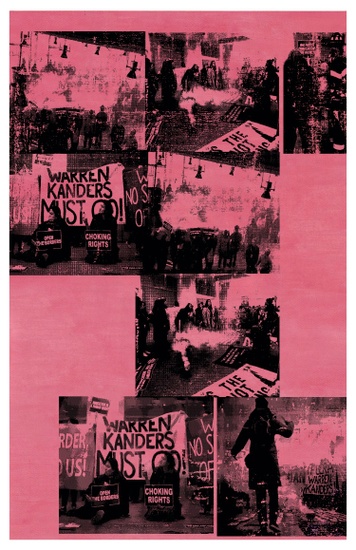

The following posters are from Decolonize This Place’s “9 Weeks of Art and Action,” March 22, 2019–May 17, 2019, which coincided with the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again and lead-up to the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Courtesy of MTL Collective.

ND

The “9 Weeks of Art and Action” at the Whitney is a good example. Each week’s action focused on a different struggle. The whole idea was going from crisis to decolonization. In week eight, the action started in East New York and moved all the way to the museum on the subway. It was like a party on the train, with different groups coming on at different stations, doing mic checks, talking about gentrification and about the policing of the MTA. The Chinatown Art Brigade was also doing a tour in Chinatown around gentrification, which eventually ended at the Whitney. And, of course, gentrification and policing are extremely tied together—most groups working on degentrification are also working on demilitarization. This was also in 2019, when Darren Walker of the Ford Foundation was expressing support for the idea of humane prisons and the city’s plan to replace Rikers with new jails. These actions show that museums are not exceptional places. They have been made into exceptional places by a logic that says this is culture, this is where aesthetics are formed, this is a special place for people who have taste, this is a place where citizenship is formed and where it is decided who is civilized or not. But once you look at how museums function, how the art economy functions, their relationship to the land, and the violence perpetuated by these institutions in the form of gentrification, the myth of the museum is shattered. And if those linkages aren’t clear enough: consider the remains of folks who died in the 1989 MOVE bombing in Philadelphia that were found in the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Museum. This is, literally, the police handing things over to the museum. The museum is not separate from the mechanisms of state violence.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay takes us through the ways modernity is linked to colonial violence in her video “Modernity is an Imperial Crime.” Modernity—and modern art specifically—is based on plunder and dispossession. “Their archives are receipts.” But Ariella also talks about the potential history of the museum—what would it mean to dismantle the institution, to actually look at its history. Once you start looking at it, you start seeing that the project of nation-building is also part of the museum. She also points out that MoMA did an exhibition in 1964 called Art Israel, responding to the continuation of the Nakba from the technical formation of the state in 1948 through the 1967 Six-Day War. In this exhibition we see the role of the museum in legitimizing settler colonization. This is the kind of exceptionalizing that we’re talking about. And as far as connecting the museum to policing: Stefano Harney recently remarked, “the museum is also a precinct.”

Apart from the financial mapping, you see it even in the aesthetics of these institutions. Take the role of MoMA trustee Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, who was the topic of our Strike MoMA action on June 4, 2021. Cisneros’s husband Gustavo Cisneros sits on the board of Barrick Gold,a mining company in the Dominican Republic. The Cisneros Collection—which Kency Cornejo calls the MoMA of Latin America—is anti-Black and anti-Indigenous, based on a particular idea of modernism. (It also donated hundreds of works to MoMA in 2016.) So the collection feeds into a sense of aesthetics, and what aesthetics means, and what taste means. All these “diversity, equity, and inclusion” measures allow museums to further capitalize on aesthetics. White supremacy is in crisis—that’s part of your question—these institutions are in crisis, and we’re seeing them close down or fall apart, but aesthetics are also in crisis, and aesthetics are deeply connected to how we live. Nelson Maldonaldo-Torres said that aesthetics is about how we live in time and space, how we sense the world, how we think about beauty, and how we actually react to it.

Especially in settler colonial nation-states, you’re living a settler aesthetics every day. The structure of society—your home, your school, your university, your desires—is captured by settler colonization. So aesthetics is also desire. And all of that is part of this project. As for the university—we know that so much of knowledge is stolen, and so much of the infrastructure of these institutions was built by stolen bodies. But aesthetics can also offer a way to break out of that colonial way of living and thinking. So a lot of the actions we’re talking about are not just targeting the financial record of institutions, but are actually trying to dismantle colonial environments. We usually get framed as protesting bad money, but it’s so much bigger than that. It’s about going up against a whole structural system and asking how we can exit it, how we can build our own system, how we can reorient toward each other, not the institution.

NG

One of the premises of this book is that institutions can no longer conceal their dependence and investment in predatory systems. Is it still believed that museums are neutral institutions? Or who is inclined to believe this? It seems to me that, yes, there are still many arts administrators, critics, and artists who want to believe in the inherent goodness of art and art museums. But it’s hard to deny that the cracks are showing and that some of these institutions are beginning to collapse. Do you see this as a sign of transformation, as the ground for new kinds of strategies? How should we interpret this moment?

AH

Again, our goal when we intervene in the museum is training and learning—it’s about trying to understand how power relates, to figure out what is concealed, so that we can also figure out how to move in the world without comporting ourselves to these institutions. And it’s about trying to shift the conversation that we’re so tired of fucking having. We’re starting from a place where we want to get free, but we need others to get free with us. Not everyone is as engaged or as invested, not everyone has the same skin in the game as we do. So then how do we do it?

The only way we can protect ourselves and protect the project is to keep moving. If you have a stationary position, or a stationary target, you get too narrowly defined, when, in fact, what we’re trying to do is engage people’s imagination and threshold of freedom, including our own. Part of learning and moving is acknowledging that not everyone is on the same page. And that’s essential. There’s a spectrum. And people’s modes of engagement produce a politics that then moves the spectrum. We’re interested in that spectrum. We’re interested in the spectrum continuing to move. And we’re interested in people who are comfortable feeling unsettled, and who are willing to ask questions that they thought were settled.

I think people now know that museums are not neutral. I think the gatekeepers of museums know that museums are not neutral. And this is really who we’re talking to. We have to take Fred Moten seriously when he says that most people in New York City don’t give a fuck about MoMA. So then why do we give a fuck about MoMA? In part because we love art, in part because we know the harm that it’s doing, in part because we need to gesture to something concrete in order to call into question the terms upon which the conversation has been had for so long. And that’s really what Fred was talking about in our last back- and-forth. He was saying, “if you don’t like it, just fucking leave.” And we keep saying “it’s not that easy.” We don’t want to leave by ourselves. You know what I mean?

The issue really isn’t whether museums are neutral. We’re past that point. The issue is whether we’re willing to recognize that any claim imposed on the institution will largely be one of assimilation.

ND

It is clear that when you have people like Larry Fink—who funds the New York Police Foundation—also sitting on the board of MoMA (and probably other institutions), you have to move beyond inclusion and beyond assimilation. What we’re seeing is actually a fight between assimilation and what’s happening on the street. And this fight is also happening in institutions. Right now there’s a real crisis, especially for BIPOC artists and thinkers, around whether you participate in the art institution. The Whitney Biennial was a good example of this struggle—the museum is part of this violence, yet this was also its most diverse show. Should we be happy with that? Or should we push to completely dismantle the institution and see what we can do with each other instead?

Inclusion in a system that’s already built on violence is not going to produce results, not going to end the violence, it’s just going to push it onto someone else. Especially in the United States, assimilationist projects do not include the anti-imperialist dimension of struggle. As part of a liberal framework, institutions are having conversations around reform within the context of the nation-state. And in this case, within the context of a colonial project. So do you actually want inclusion in these systems? What we’re saying is, we don’t. And I think Fred Moten said it: he does not want to take over the plantation, right? He’s not interested in keeping with the plantation.

Dismantling places like MoMA also produces resources. Like Ariella said, their archives are receipts. So we can actually look at it collectively and acknowledge it is going to be a process—abolition and decolonization don’t have an end goal. But we know where to start. The history of the institution, the land, the people who built it (Rockefeller oil money in this case). It’s endless—if you look at the Whitney, you would probably find the same things. The American Museum of Natural History—it’s off-the-chart looting. The violence does not stop. And with “diversity, equity, inclusion,” these institutions are yet again more interested in benefiting off of our pain than engaging with our desires. Because if we actually have a conversation built on our desires, it will unsettle their power. So assimilationist projects are very limited in what they want to achieve. As to whether art institutions are in crisis—well, if they fall apart, they fall apart.

You also have institutions like MoMA, in the context of COVID-19, applying for emergency funds and at the same time, laying off staff. It’s eerily similar to the 2008 financial crisis when banks took money but never distributed it. In fact, Eyal Weizman was telling me about how Goldsmiths has adopted this IHRA [International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance] definition of anti-Semitism, which basically forbids you from doing solidarity work with Palestine. They had at one point said if you do not sign this IHRA, your institution won’t get its COVID money. This is happening in the UK but also here. CUNY also went through this IHRA stuff.

This crisis will keep happening, as Amin already mentioned, and counterinsurgency will keep trying to crush any potential transformation. And we saw that with the George Floyd moment, right? The kind of revolutionary potential that it sparked is not what panned out. Dylan Rodríguez has done work to show how NGOs are part of counterinsurgency projects—and we’ve actually experienced that in our movements. Museums and universities function as counterinsurgency mechanisms as well. It’s not just state institutions. At this point, people—you know, normal people—are part of counterinsurgency, because it’s ultimately about a way of thinking. Right now people are extremely unsettled with, let’s say, the idea of a post-MoMA future, a future where MoMA is irrelevant. The same unsettling is true when we talk about a post-NYU future and post-Harvard future as well. Why do we need institutions like these as the gatekeepers of stolen knowledge?

Museums and universities continue to strengthen themselves as well—we saw that with MoMA. It turned into a highly-militarized fortress during the fourth week of action. The museum completely functioned as a nation-state. It was engaged in some serious psychological operations. They profiled organizers. They spoke in scripted language— claiming “protesters were violent.”

I do think we’re at this point of decline and failure, and not just the failure of Western thought. Its impact on climate, and what colonization and capitalism have done in terms of extractivism, is also at stake. There isn’t a single part of the world that is untouched. So at this point, it’s about everything: it’s about how we live, it’s about survival, it’s about existence. As the Zapatistas say: against death and for life. We’re seeing extractivist projects everywhere with deep impacts on communities and ways of living. But now, we’re also seeing more people say no to this kind of development and progress, saying, “I do not need your modernization, I do not need your progress.”

NG

It’s interesting to see how these institutions react to these shifts. In some ways they react differently. But, as you say, there is still a tendency toward assimilation. Museums see a need to consolidate their power in order to resist what is happening. I work at the San Francisco Art Institute. The institution has almost closed repeatedly over the last several years and again at the beginning of the pandemic. In this instance, they really preyed on people’s vulnerability—everyone was afraid they would lose their jobs, and that students on visas would get shut out. In the end the school pushed out any staff who was considered expendable in order to remain open and they paint this as a success. They released a statement saying, “this is the 150th anniversary of this institution, and we will exist for another 150 years.” Aside from the question of whether we should be celebrating this predominantly white institution founded in California in 1870, the school’s projection of confidence about the future is very concerning.

AH

One thing I want to just linger on for a second is that there’s something reductionist about how we’ve been thinking about institutions. When we say strike MoMA, abolish MoMA, abolish museums, when we say that museums are adjacent to prisons and precincts—this is a way of saying we need to extend abolition, regardless of the framework you’re coming from, as an Indigenous person, as a Black person, as a formerly enslaved person. Abolition extends to museums, and therefore museums are not exceptional in the struggle for abolition. We’re saying abolish the terms of engagement. We’re not saying abolish the building or the infrastructure, although you could burn it all down. We’re saying that you can leave MoMA while being in the building and collecting your check. You can work for MoMA and work toward burning down MoMA. You can do both. I don’t know why people need to have such an allegiance to an institution that is actively killing people. That’s what I don’t understand. No one’s saying boycott MoMA. No one’s saying, do a grandstand against MoMA and starve in the process. What we’re asking is why ignore the fact that MoMA is complicit and actively participating in hiding people and washing money, in taking resources from the city, in obscuring struggles, in pitting us against each other, in defining the public as one that reifies the separations among us and that perpetuate individuation?

NG

We’ve talked around how colonial logics basically legitimize curatorial work. What about criticism? I am thinking of the ways that journals and supporting institutions are financed, but also the very projects of knowledge and exposition to which criticism contributes. Is there a way to produce critical writings that do not support the soft powers of settler violence, extraction, and confinement? Is there another way to engage aesthetics? You’ve both talked many times about the need to think about aesthetics and, as you were saying earlier, Nitasha, about the need to understand aesthetics as a way of describing the times and places in which we live. Can we think about writing as a form of political education? How can critique be transformed into decolonial praxis?

ND

I want to reintroduce this idea of training in the practice of freedom. The process of transformation is one that gets embodied through practice. And our own kind of journey has been one of failures and successes. One of my favorite actions was the third anti-Columbus Day tour that we did at the American Museum of Natural History, because everybody came in and did their own thing; it wasn’t a coordinated tour. So you would go to one part of the museum and there was a group of Anishinaabe women drumming in front of their ancestors; you would go to another part and there was a poetry recital; or there was a workshop on accountability for the ways institutions show colonization and enslavement. Each place in the museum became a way to relook at history and all these pockets of time and space against colonial logic emerged. These are the spaces of transformation that one embodies and learns from. You learn because you’ve actually been with other people. It’s not an individual project but a collective sense of being together and asserting your presence through beauty and voice and all of these different things.

In terms of critique and writing: writing is really an aesthetic project, just as art is an aesthetic object. I think writing can definitely inspire a kind of political education. We use writing as a mode of pedagogy. We always distribute pamphlets in our actions, because we think about movement-generated art, and movement-generated thought, and movement-generated theory. A differentiation between theory and practice does not exist. I don’t know if you could call it decolonial praxis, because decolonization inherently means acting and thinking together. It is not something that happens in a university while doing your PhD, or when you’re a professor. It’s not cased in that settler system of knowledge. It’s an extremely embodied practice that requires our bodies to be present.

We don’t think that there’s a difference between art organizing and pedagogy. For us, they happen simultaneously, and they’re part of the same project. They speak to each other and they come from each other. Sometimes an image inspires something or writing inspires an image, and it’s a back-and-forth. We have to go against the training of rationality that comes with Western thought. Aníbal Quijano and other Latin American folks have done a really good job at showing us the possibility of decolonial worlds, echoing what the Zapatistas always say: one no, many yeses. So when we say no to MoMA, we’re saying yes to the many other spaces of pedagogy, art, and thinking that are out there.

The one last thing I want to bring up, which we haven’t talked about, is the idea of private property. Settler societies begin with private property as it relates to the land, but it’s literally part of every facet of society, from your house, to your education, to your art. Whatever it is you’re looking at, what is its relationship to private property? When you talk about art, you have to shift it from the individual genius of the artist to its relation to the market, for example. It’s the delinking of things from private property that becomes really important. The moment you delink, I think there’s a space of freedom for making art and writing and thinking and producing knowledge.

Language is also part of this system. We’re talking in English, but we can and do think in different languages. We’re translating constantly. Being engaged in a kind of conversation that produces movement- generated theory, art, action that reorients us to each other (versus to an institution) is what we need right now—a kind of thinking and speaking that is not based on borders and nation-states but is ultimately much more planetary. Especially as we deal with the kind of crises that these institutions, corporations, governments have put all of us in—the struggle to survive.

AH

I would just add that the training and practice of freedom is also about the diversity of aesthetics. Maybe you can talk a little bit about that, Nit.

ND

Diversity of aesthetics is like diversity of strategies. Aesthetics is tied to the way we live and there are so many different ways to live. The struggle in life is also a struggle over aesthetics. So diversity of aesthetics is about being in action, it’s an action-oriented phrase. I already mentioned the third anti-Columbus Day tour. That was a diversity of aesthetics approach. Rather than all stepping into the same anti-colonial frame, it was about mic checking together, taking the floor, and enacting and embodying new frames based on our own aesthetics and histories. And even though I might not understand your language, we share in the struggle: our wounds are interconnected, our desires are interconnected, so our feelings are interconnected. You’ll be surprised how much we all understand each other, even if we might not, you know, speak the same language.

10

Acknowledgments

It is my hope that this book has provided a critical frame for redirecting the capacities of aesthetics, creativity, and collectivity to foment social change. Already I have had the privilege of thinking and writing in the company of scholars, activists, and artists whose radical social commitment bridge the space between critique and radical praxis.

Foremost among my collaborators is Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt, whose unwavering vision and supportive intellectual friendship made this book a reality. Thank you.

Amin Husain and Nitasha Dhillon generously spoke with me about the praxis of decolonization and abolition. I am profoundly grateful for their collaboration and honored that they chose to share their vision and critical insights with the readers of this book.

Thank you also to James Graham for joining Isabelle on the initial editorial engagement with this manuscript. Both Isabelle and James were early and enthusiastic supporters of this project. Thank you to Joanna Joseph at CBAC for being part of the conversation; to Stephanie Salomon for copyediting; and to Luke Bulman for the fantastic design of this volume.

This project would never have come about without the generous mentor- ship of Kandice Chuh, as well as Peggy Phelan, Macarena Gómez-Barris, May Joseph, and Claire Bishop, who have supported my research and writing at various stages over the last several years and modeled the kind of critical politics this book strives to emulate. Thank you also to Eric Lott, Cindi Katz, Peter Hitchcock, Neil Smith, Robert Reid-Pharr, Wayne Koestenbaum, Jennifer Telesca, Michael Kahan, Robin Balliger, and Gwen Allen. My friend and teacher Meena Alexander who died in 2018; many of the ideas around transnationalism that appear in this book came out of conversations with her over several years at CUNY and later at the New York Public Library’s Berg Collection.

For thinking with me about the utility (and limits) of political theory in art and media practice, I must thank Jason Fox, Toby Lee, Josh Guilford, and Bonnie Honig; Helene Kazan, Amin Husain, Nitasha Dhillon, and Ariella Aïsha Azoulay; Rachel Stevens, Martin Lucas, Irmgard Emmelhainz, Rayya El Zein, Kareem Estefan, and Cecilia Sjöholm; and especially Tania Bruguera and Greg Sholette.

For reading early drafts of these essays, thank you to S. Topiary Landberg, Anika Jade Levy, Bryce Renninger, Ari Brostoff, Alex Wermer-Colan, and Yi Jing Zhou, as well as Richard Dyer, Karen Van Meenan, Paul Fermin, Greg Stuart, Colin Beckett, and Tess Takahashi. Thank you to Maria Stracke, Mike Granger, Melissa Phruksachart, Anahí Douglas, Annie Dell’Aria, Sarah Kanouse, Monica Bravo, Jennifer Scappettone, Rachel Heimen, Rose Salseda, Lucia Stavros, Nicole Charky, and Jennifer Larson. Special thanks to Margaret Marietta Ramírez.

I continually learn from art activists, whose work has animated my thoughts and my conversation with others. My students at Pratt, Stanford, and the San Francisco Art Institute have challenged me to think harder, to convey my ideas more clearly, and to bear in mind the urgencies of this time. I dedicate this volume of essays to them.

Finally, heartfelt thanks to my family and to my partner Andrew Rosenberg for joining me in a life of art, politics, and community making.

Columbia Books on Architecture and the City An imprint of the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation

Columbia University 1172 Amsterdam Ave 407 Avery Hall New York, NY 10027

arch.columbia.edu/books Distributed by Columbia University Press cup.columbia.edu

After after Liberalism By Nicholas Gamso

ISBN 978-1-941332-68-9

Graphic Design: Office of Luke Bulman Copyeditor: Stephanie Salomon Printer: Musumeci, Italy Paper: Kolibri b/g and Munken Polar Rough Typeface: Lyon and Untitled Sans

© 2021 by the Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the publisher, except in the context of reviews. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify the owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

This book has been produced through the Office of the Dean, Amale Andraos, and the Office of Publications at Columbia University GSAPP.

Director of Publications: Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt Associate Editor: Joanna Joseph

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gamso, Nicholas, author. Title: Art after liberalism / Nicholas Gamso. Description: New York, NY : Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “Art after Liberalism is a study of creative practice at a moment of converging social crises. It is also an account of the possibilities that may emerge from these conditions. The apparent failures of liberal thinking mark its starting point. No longer can the framework of the nation state, the figure of the enterprising individual, and the premise of limitless development be counted on to produce a world worth living in. No longer can claims of benevolent inclusion, or the premise of the neutral public sphere, pass for something like equality. It is becoming increasingly clear that these commonplace liberal conceptions have failed to improve life in any lasting way. Indeed, they conceal fundamental connections to enslavement, conscription, colonization, moral debt, and ecological devastation. The essays in this book attempt to register these connections by following itinerant artists, artworks, and art publics as they move across comparative political environments. The book thus provides a range of speculations about art and social experience after liberal modernity.” —Provided by publisher. Identifiers: LCCN 2021034892 | ISBN 9781941332689 (paperback) Subjects: LCSH: Art—Political aspects. | Liberalism. Classification: LCC N72.P6 G36 2021 | DDC 701/.03—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ 2021034892