Introduction

print editionIntroduction

print editionPreface

print edition1

print edition2

print edition3

print edition4

print edition5

print edition6

print edition7

8

print edition9

print edition10

print edition11

print edition12

13

print edition14

print edition15

print edition16

print edition17

print edition18

print edition19

print edition20

21

print editionEpilogue

Backmatter

7

Fallen Cities

In Arabic conversations, “the situation” ( الوضع) is used to indicate prevailing political, social, and economic uncertainty.1 Those who use the phrase rarely specify what situation they are referring to. Has there only ever been one situation? The multiplicity implied in its nonspecificity binds one speaker to another in an implied assumption that is both intimate and collective. A former Baathist Phalangist, Communist, or Pan-Arab Nationalist no longer. Not yet a martyr.

Just a shared hesitation to speak the language of parties, names, and events. In their place, an empty term that stands for all possible parties, all possible names, and all possible events: “the situation.” Like an incantation, if you repeat it enough times, a million tiny acts of solidarity will add up to a collective perception. Curiously, this affective precision is secured by the complete absence of content in the statement. “The situation” can literally refer to anything. Its task, however, is not to convey information but rather to forge agreement that the predicament is so self-evident as to require no further explanation—“it’s bad,” “we” are “in it,” “together.”

This “we” is its work. Perhaps nothing forges solidarity like a shared sense of malaise. Perhaps it all depends on whether this shared sense is exhausted by its capture as malaise. In any case, whatever it lacks in specifics the term more than makes up for in scope. Indeed, the seeming inescapability of the situation colors every question and every judgment on the Arab City. Like the “Arab street,” a foreign policy term now used as shorthand to describe popular Arab sentiment, the “Arab City” appears perpetually aggrieved and inflamed. Undoubtedly, the fact that Arab identity, Arab cities, and Arab streets are constituted as certain kinds of problems, ones that command public interest, invite debate, and are worthy of discussion, cannot be separated from the multifarious geopolitical investments in the region. After all it is Arab identity, not some other identity, that is at stake here, and not only for Arabs, since the question has for some time merited discussions of a broader and certainly more pernicious nature within colonial states with respect to their former empires. The streets and cities of other communities are mainly matters of interest for those communities, as well as those whose job it is to be interested in such things; they are simply not burdened in the same way or by the same fears. To enter into this particular debate then, even as a strenuous critic, risks accepting its frame and reactivating the habit of posing questions according to these terms.

How to proceed then? One might take “the situation” and the commonality of its use in everyday speech as a sign of caution and equivocation, a reluctance to betray positions or enter into public dispute out of fear of recrimination. But why insist on seeing this expression as a lack rather than an act of everyday resistance? Its compulsive repetition is evidence of an attempt to suspend representation long enough to allow mutual sympathies to form. If the statement is not framed as lack, failure, or disavowal—and the suggestive ambiguities it offers are pursued—then another entry point into questions about the Arab City can become possible. This other entry point would not presuppose either of the two terms that guard its entrance, either “Arab” or “city,” let alone the colonial legacies that mark the significance of their conjunction beyond the Arab world. So instead of starting with its refusal to specify, let us try to start with its function, which is to forge a collective sentiment. These sentiments, as articulated through the countless expressions of popular sovereignty that have been heard in the last few years, suggest a nuanced understanding and sensitivity to the relations between implicit and explicit registers, as well as to the tension between affect and its capture through systems of representation. After all, the implicit affective solidarity produced by

الوضع / الحالة al-wad’a [the situation]

can suddenly crystallize into a perfectly explicit revolutionary demand:

شعب‘ al sha’ab [the people]

يريد‘ yurīd [want to]

إسقاط isqat [bring down]

النظام an-nizam [the regime].

I would like to examine the way that new collective sentiments are expressed, formed, and made explicit within contexts of social transformation. Architecture has a fundamental role to play in these processes, and the examples cited above provide new insights into how we might understand the political function of architecture. Beyond an attention to the intrinsic precarity of these utterances is their urgent need to acquire a life beyond their performance in everyday conversation, to take forms that survive moments of “popular jubilation,” as Jonathan Littell recently put it.2 When the chorus of voices falls silent, it is urgent to seize possession of all the passions of resistance, the investments, the sympathies, and the sentiments, and to finally discover what structures best secure their fate. It’s a question of desire: how to produce it, how to satisfy the demands that flow from it, how to secure this satisfaction into the future?

Architecture has a fundamental role to play because it is able to contribute something essential to the durability of new social diagrams—an impersonal form. By stating that “the nature of contemporary power is architectural and impersonal, not personal and representative,” the anonymous collective the Invisible Committee point to something that is growing clearer in leftist thought—the need for a constructive political architectural project.3 This is not to say that personality has nothing to do with politics, or that we are done with the significance of the face, or manners of speech, or charismatic leaders, but rather to indicate the way that contemporary forms of power cannot be understood without a serious examination of our imbrication in material and technical worlds and the subtle yet persistent solicitations these worlds make on life.

To make this proposition more concrete, I want to draw on a moment in Lebanese history that was as unlikely as it was decisive. Commissioned by a proto-state, named after a zaim (leader), and designed by a part-time communist and full-time Carioca, the Rachid Karame Fair and Exposition project in Lebanon by Oscar Niemeyer is an object lesson in architecture and the problem of nation-building. The project depended on the model of the state that gave birth to it, one that conceived of the nation as something plastic, one that reserved the right to intervene in that plasticity in order to shape it. But already by the 1970s, when an aggressive return to laissez-faire markets and the civil war interrupted the nascent movement toward a social welfare state, Lebanon’s political leadership was no longer willing or able to secure the conditions in which the project was supposed to operate.

Northern edge of the Rachid Karame Fair and Exposition entry plaza, showing rows of unadorned flagpoles. The plaza datum directs visitors toward an inclined ramp and the entry pavilion.

For many, the sense that individual projects fail to produce social transformation is troubling, if familiar. Maybe because it mirrors the secret presupposition that individual works effect social transformation in the first place. At the very least, it raises the question of architecture’s contribution to social transformation. In the case of the project in Tripoli, the failure to build a new Lebanese state, legitimate institutions, and a workable idea of citizenship makes broader questions regarding the instrumentality of architecture and its contingency within social movements more explicit rather than less. Still, this judgment of failure can only be made from the perspective of the 1960s Nahda, or renaissance, and its commitment to socialist, nationalistic, and pan-Arab programs.4 A contrary position could be taken, that the inability to take a monolithic form in a country without a hegemon was what lent Lebanon its peculiar ability to endlessly absorb regional pressures: not quite a state in any real sense, not even a peace—more a permanent, uneasy truce.

In either case, nation-building is an impossible burden for a work of architecture to carry when extracted from the political, financial, and institutional context that commissioned it, lent it sense, and struggled to sustain it. More useful than any appeal to Arab-ness, then, is to examine the concrete processes of experimentation in which social diagrams are produced and how the instruments of modernity are taken up and modified, reactivating and mobilizing archaic structures like feudalism. By social diagram, I refer to implicit norms and explicit spatial and institutional forms that work together to produce, stabilize, and secure specific relations of power, including the production of national identity.

In doing so, a more consistent, if transversal, genealogy can be cut through different claims for social change regardless of their periodization or their supposed regional or linguistic commonality. By way of Niemeyer’s intervention in Tripoli, I propose that the diagram is what secures the operation of the work. It is what sustains the drive for transformation, what allows it to persist. Finally, I suggest that this work sets out to manufacture a certain kind of subject. The era of nation-building projects was directed toward an imagined subject to come, one whose natural affinity to family and community had to be reoriented toward the promise of citizenship and national belonging. In this process, one kind of collective sentiment had to be replaced by another: familial, communal bonds would need to dissolve and national ones would need to emerge to take their place. However, there was a challenge. The nation did not exist. It would need to be invented. In the case of Lebanon, the reformist nature of this project meant that this transformation would take on an inherently pedagogical nature. The state would draw heavily on urban, infrastructural, and architectural projects to dissolve filiations at a communal scale in order to better establish it at the scale of the state. Exactly how this was supposed to be accomplished is a matter of importance not only because the era was such a crucial juncture in Lebanese history, one that belies the catastrophic upheaval soon to follow, but also because it raises questions of a broader disciplinary nature.

THE DOME IN THE PARK

Returning to social transformation via this refrain, “the situation” requires that we distinguish between two different aspects: an interpretation that signifies some lack on one side (the inability to specify) and a direct intervention in the field of subjectivity between the speakers on the other (implying a common perception). One could say that architecture is still far too indebted to the first at the complete expense of the latter. In order to explain this and justify why it is relevant to a discussion on architecture, a digression through theory is necessary, primarily to differentiate between signifying and a-signifying operations of signs. This distinction, which comes from the work of Félix Guattari, refers to those signs or aspects of how signs work that are independent of what they mean. Guattari uses the concept to break the dominance of structuralist linguistics and psychoanalysis on our understanding of the unconscious. With respect to the statement “the situation,” it works to mobilize certain kinds of passions prior to the allocation of positions or the articulation of identities. In fact, we could say these substrata of affect become a kind of raw material for the subsequent formalization of linguistic statements. The difference is crucial: the absence of the referent with respect to the meaning of “the situation” produces the conditions under which a new referent (solidarity) can emerge. The condition that is being produced by the statement is nothing less than a small but precise intervention in the formation of subjectivity itself. The concept of the a signifying operation of a sign invites us to attend to processes of subjective transformation that exist prior to or alongside understanding—that is to say, prior to or alongside of the recognition of meaning in signs.

Dome for experimental theater and music, Oscar Niemeyer, 1975. Photograph by Jack Dunbar.

Interior of the theater dome for experimental theater and music, Oscar Niemeyer, 1975. Photograph by David Burns.

Acknowledging both the operational and semantic character of signs through this spoken example offers a way of thinking about architecture, especially the idea that “intelligibility” should be the dominant mode of reception. Consider the example of the dome, a paradigmatic element within Christian and Islamic architectural traditions. It’s an enduring form whose resistance to transformation makes it particularly qualified to reflect the immutability of sacred and profane images of the cosmos. Think not only of churches and mosques but also of observatories and planetariums. Responding to historians Rudolf Wittkower and Heinrich Wolfflin—who argued that dome of central-plan church was the ideal embodiment of Renaissance thought—the architectural critic Robin Evans suggests that, within the Christian tradition, these structures and the frescoes painted on their inside were evidence of nothing less than an architectural and artistic struggle to reconcile contradictory theological concepts of heaven and earth.5 After all, the heavens were composed of orbiting celestial bodies arranged in concentric spheres around the earth, yet all power—including divine power—radiated out from a central point. The dispute, as Evans puts it, was between envelopment and emanation. Each position embodied distinct and sometimes antagonistic social, theological, and political claims about the location of God with respect to man. According to Evans, the achievements of Brunelleschi or Raphael lay in their ability to literally give form to the contours of this dispute by bringing these differences into proximity and holding them in a space of coexistence. Somewhat perversely, when it comes to domes, the very recalcitrance of their geometries has only encouraged rather than limited this kind of interpretation and speculation. For Wittkower and Wolfflin, the dome embodied perfection, while for Evans it embodied dispute. Yet all agreed that the dome must be interpreted. What was at stake was never signification as such, only what was signified.

Indeed Wittkower, Wolfflin, and Evans might well be justified in framing this problem in terms of codings and decodings of meaning insofar as such framing describes how the work was often reasoned by its authors and received by its audiences. The legacy of this question and its hold over contemporary accounts of architecture is of more concern. The issue of Arab identity and its architectural representation is a case in point, since it is still posed in terms of tropes and their representational adequacy. So the debate around domes or even the problem of appropriate and inappropriate orders now persists in the mashrabiya, geometric tiling, pointed arches, and vaulting that are deployed to signify “Islam” or “Arabness” along a spectrum ranging from very subtle and discreet (good) to vulgar and kitschy (bad). Consider the Lebanese Pavilion in the Rachid Karame Fair and Exposition site: a square-plan, open auditorium framed by a colonnade using a pointed arch. Most will recognize that this particular form refers to Ottoman traditions, of which there are many examples in the area. Some will not grasp the allusion, however, since the sign’s legibility is dependent on the observer’s prior knowledge. I happen to like the arches; others will find them unadorned, and most will probably pay them little attention. In any case, the form is supposed to signify cultural belonging and history.6

Architecture works on us and through us regardless of whether we “get” it, regardless of its intelligibility, and regardless of our capacity to appreciate its tropes or derive pleasure from their modification. This is an important political point; at stake is nothing less than a claim about what architecture does outside of architectural discourse—what it does to nonarchitects. Buildings are primarily nondiscursive objects even if they are always ensnared in discourses of every kind. This is why the concept of the diagram is so relevant here. It allows us to place the nondiscursive, a-signifying aspects of architecture into relation with the discursive, signifying aspects—architecture’s instrumentality is always bound to the nonarchitectural. Diagrams are not manifested literally as specific tropes, or even as systems of organization. Neither the pilotis, the free plan, the New York frame, nor the Dom-ino is diagrammatic in and of itself, nor can they be ever considered in purely architectural terms, whatever that might mean. They only act on the social body as intended when they are secured by a constellation of cultural attitudes, laws, customs, regulations, and other requirements. The discursive and nondiscursive elements work together within any diagram. The panopticon would simply be a damp, round building with a tower in the middle without the transformation of penal codes, prison reform movements, the judiciary, and a police force. The modern domestic unit would just be an odd way of strategically segregating and bringing together bodies without the “charitable” incentives of philanthropic organizations, the regular assessments of housing inspectors, or instruction manuals for poor families. Do prisoners or members of a nuclear family need to recognize these histories in the disposition of rooms and arrangement of functions? Will the disposition of rooms and arrangement of functions cease to act on their habits, pattern their socialization, or structure their gender roles if these histories are unintelligible? In other words, absent an understanding of its sociopolitical motive, will the prison cease to shape them as certain kinds of human subjects?

To answer this, consider another dome. In the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli, in the park-like Rachid Karame Fair and Exposition site, there is a dome that wears its dereliction a little better than the buildings around it. Some 62 meters wide, its slightly squat, not quite hemispherical shape gives little away. Only the acoustics and the sunken orchestra pit inside betray its uniqueness. The dome was supposed to be a venue for experimental theater and music, a program that makes it possible to calibrate the precise distance between the present situation in Lebanon and the past situation in Lebanon.

Back when it was still called the Syrian army and not yet “the regime,” thousands of soldiers were stationed in temporary barracks alongside the dome. These days, because of the situation, only the especially curious venture in. A one-hour drive from Tripoli will take you to the top of the Lebanese ranges, where you can look out to what used to be Syria and listen to the sounds of shelling from the Qalamoun Mountains across the Bekaa Valley. From either vantage point, the sense of resignation is hard to shake. Nevertheless, these lost modernities deserve closer scrutiny. If a system of subjectification was built into the fair and exposition, it is worth asking exactly what kind of techniques would be addressed to the bodies and characters of those meant to populate the project? What was specific about architecture’s contribution to the project of nation-building during this period? Is it possible to account for the imagined instrumentality of the project without relying exclusively on a semantic interpretation of its tropes?

TECHNOLOGIES OF NATIONHOOD

The exposition type played a critical role within nation-building projects throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century, exemplifying concepts of citizenship and cultural belonging. The Rachid Karame Fair and Exposition site draws on this history, especially its appropriation during the postcolonial era. Surrounded by a four-lane road and nestled in the elbow of a freeway connecting Tripoli to Beirut, the 1.1 kilometer long elliptical site might pass for the world’s largest roundabout were it not for the occasionally beguiling structure poking past the canopy of trees. The exposition and fair facilities occupy maybe one-third of the site, with the rest set aside as an imagined parkland for the metropolis that never materialized around it. The 750 meter long expo hall is the most dominant element. To its east lie pavilions set in gardens, most of which were intended for some form of ongoing cultural production. Commissioned in 1962, the project depended on the brief appearance of something resembling a social welfare state, in which large-scale public works were seen as integral to perceptions of political legitimacy and therefore to nation-building. By the 1970s, however, pan-Arabism, which first came to prominence with Nasser’s regime in Egypt and Gaddafi’s proposal for a Federation of Arab Republics, was on the decline. This indicated a regional shift away from secular and socialist principles toward sectarian political alignments. Military defeats and economic stagnation contributed to widespread discontent in the Arabic-speaking world. In Lebanon, the contraction of the state, the withdrawal of government from social services, and an inability to implement electoral reforms or build stable institutions coincided with the extreme regional destabilizations occurring as a result of the conflict between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), now operating from Lebanese bases.

Most exposition histories focus on the organization of the exhibitions and the strategies used to order, represent, and juxtapose different cultures. At times, scholars will turn to the technical innovations used in the construction of the exposition hall or within the exhibits themselves. Niemeyer’s proposal for Tripoli is different from the prototypical world’s fair or international exposition in that it combines an exhibition hall with buildings dedicated to cultural production within a landscaped urban complex that was intended to be used as a model for structuring the growth of a city. These four elements—the exposition hall, the cultural pavilions, the park, and the urban plan—should be understood as complementary components within a nationalistic, pedagogical project.

There are two main forms of movement through the site corresponding to the linear organization of the exposition hall and the placement of the pavilions. Niemeyer constructed a series of ramps and elevated vantage points that encourage visitors to continually withdraw from the mass and survey the crowd before returning back down to the ground. Here, the crowd could see itself seeing and being seen. Outside of protests and demonstrations, organized public gatherings of this scale were unprecedented, and the effect of finding oneself caught in this reciprocal spectacle would have been quite powerful. Being shaped here was not just architecture; that architecture forged an audience that could, in the vastness of its own spectacle, become self-aware.

As Lebanon urbanized during the colonial period, asabiyyah (an Arabic term referring to social cohesion within a community group) and feudal familial ties that had traditionally structured sectarian belonging persisted in response to a highly competitive capitalist environment and the insecurity such an environment produced. Old networks of patronage remained important in the absence of a legitimate state able to insure the poor against the difficulties of urban life. In Lebanon, metropolitan anonymity did not dissolve feudal or familial bonds; it reterritorialized them and made them stronger. For a brief decade between the mid-1950s and 1960s, however, a concerted attempt was made to dissolve these links in order to establish them on new and different terms. The project in Tripoli is part of this history. Its organization manifests an attempt to orchestrate a set of affects and feelings of belonging that, when inscribed in dominant narratives of nationhood, would become untethered from their communal histories.

One can see the project as a machine designed to produce new relationships between the crowd and the individual, and therefore the nation—a mass orchestration of affect. However, the surplus of affect produced by the spectacle of the crowd that Niemeyer orchestrated through the ramps and vantage points would as yet remain undifferentiated, little more than a mass gripped by various existential intensities and feelings. This unformed set of affects therefore had to be captured and assigned a proper location within the social order. The crowd recently decoded must be recoded, classified, and naturalized within a national narrative. The exposition hall and the display of “characteristic” elements from the various nations assembled would inform the normalization and stabilization of a new Lebanese identity. Visitors would learn to distinguish themselves as citizens by acquiring new rules of public conduct, especially the consumption and appreciation of cultural artifacts.

Ordering the world into an image, as Timothy Mitchell puts it in his description of the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1889, produces two effects: first, a representation of national difference and, second, the extension of a colonial system of representation into the world itself.7 In Tripoli, the mass public organization of the crowd and the relation of the individual’s vantage point within it draw on the typological history of the international exposition and its curatorial organization. Through arranging encounters with artifacts, the fairground would have attempted to recode this undifferentiated population in order to define Lebanon’s newly won place among other nations. In addition to exposition planning and exhibition design, Niemeyer introduces a third element: the pavilions for cultural production and performance. These pavilions locate the citizen in a position of imagined ownership over the products of cultural activity.

We might imagine the components of the fair working together to achieve the following ends: The subjects’ communal bonds are confronted by something new—an orderly mass public spectacle, in which the subject undulates into and out of the mass producing a charge of affect that is not yet formalized. The consumption of the artifacts within the exhibition positions them in the world through a national narrative, until finally they are led to see themselves as the imagined producers of this national narrative. This is what the architectural machine accomplishes within the social diagram. The first component of the machine operates using a-signifying signs. The ramps and changes in height are not symbols to be interpreted; they intervene directly in the subjective field. Only later do the elements collaborate to produce signs whose meaning must be read. However, the precondition of meaning in the sign is the visceral charge produced within the subject. This representation of nationhood can only operate insofar as it can recode and formalize this substratum of affects and passions the spatial qualities of the project produce. However, this a-signification was only the architectural aspect of the diagram. The larger pedagogical ambition depended on more than the designs buildings have on human nature. They depended on a state that was willing to see itself as the architect of this national narrative, one in which these kinds of large-scale infrastructure projects were secured and oriented to specific ends through forms of cultural administration, curatorial strategies, exhibition programs, and the media. The weakness of the state meant that the pedagogical diagram and its technologies of nationhood did not stabilize before the onset of civil war in 1975.

AFTER THE REGIMES

Those who refuse to wean themselves off an enthusiasm for politics project insurrections without end, powers constituent but never constituted, interruptions that are never the prelude to less abject continuities.

—The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends

Of the many outcomes of “the situation,” perhaps the most accepted is the conflation of destruction and reconstruction. Revenue from luxury apartments will shower down upon those who broker peace. In war, land speculation makes a joke of military calculus. Soon enough, the rhetoric of imminent futures promised in renderings of a new Aleppo or a new Damascus will double, albeit in an architectural register, the present legacy of violence through systematic destitution and dispossession. Before these images of cities to come have acquired their final touches, however, the future they depict will have been engineered into existence through land expropriation and models of real estate speculation, through promissory notes based on calculations of future revenue according to reliable standards and estimates of return. Untethered from the realities of existing land tenures, undisciplined labor markets, and unpredictable steel prices, they will reach purely speculative heights. Like the images of many urban futures, those destined for the “Arab world” will need to become standardized before they can be bankable—the recent images from a design for a city of seven million people between the Suez Canal and the shores of the Nile being a case in point. Like a bushel of wheat or a barrel of oil, the urban future has become a standard measure. Its consistency, its ubiquity, and its reliability are what allow it to circulate. It is not surprising that promised cities act like commodities: in one sense, that is increasingly what they are. The future has to learn how to flow. Its promise has to become liquid before it can become solid. As with grain and oil, too many inconsistencies leads to friction.

Rendering of masterplan for Capital Cairo, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 2015. Courtesy of Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill.

Despite the inherent conservatism of real estate markets and the dispiriting reliability of these propositions, their colonization of imaginations is far from complete. There is no lack of discontent toward—or critique of—these propositions within architectural discourse, and certainly no lack of emotional investment in alternative futures for Arab cities and Arab streets. In Aleppo, in Amman, in Beirut, in Cairo, in Damascus, in Gaza, and in Jerusalem, there are the most startling signs of political experimentation, social movements, activism, and institution building. There are, in other words, signs of survival, resistance, and invention to be found everywhere. From experimental coalitions on human and natural rights in Lebanon to proposals for democratic federalism in Southeastern Anatolia, from feminist movements in Kurdish communities to autonomous neighborhood assemblies in beleaguered Syrian cities, we see brave and vital attempts to reimagine social ties and forms of political organization. But without access to the equivalent of what Timothy Mitchell describes as the future’s “engineering works,” it is difficult to imagine how these precious experiments of alternative social orders can be sustained.8 Discontent, critique, and desire alone will not be enough to turn aspirations into reality, because the various systems of calculation and capitalization that drive real estate development have a particular kind of durability.

The aversion toward “social engineering” within architecture or urban design has not resulted in societies that lack “engineering,” let alone societies that are more perfectly ordered. On the contrary, the result is simply societies whose order and engineering have been dictated by those who have access to the future’s infrastructure, leaving the rest condemned to precarity. The persistence and dominance of these conditions is often described as “neoliberalism,” but this term fails to capture the specificity or diversity of the many socioeconomic diagrams that it is said to encompass. Moreover, it misses the fact that it is precisely these different socioeconomic structures that normalize processes of subjectification. The stability of the links forged between foreign capital, real estate speculation, and the domestic unit, for instance, works to ensure the reproduction of social and political power in urban space. The elements that compose these diagrams—their links, their ability to persist in time, repeat in space, and shape forms of subjectivity—cannot be reduced to matters of representation and interpretation. Financial calculation, debt, and living and working arrangements secure their own reproduction because they appear as sets of norms, material constraints, and habits that function regardless of the meanings or interpretations that critics assign to them.

Perhaps the people that were supposed to inhabit the fair site in Tripoli ended up materializing fifty years later in the streets and squares of other cities? These crowds, recently gathered and too quickly dispersed by brutal counter-revolutions, insist that we question assumptions about the durability and stabilization of new social orders. The contingency of architecture with respect to these orders suggests a more careful examination of histories of subjectification as a pedagogical project. Such an inquiry would not simply entail escaping from signification but rather describing the feelings, codings, and structures in which signifying and a-signifying elements cooperate within a political project. The institutionalization of social movements might be one place to start, and architecture’s impersonal form might have much to contribute. After all, when regimes are brought down and after the people have expressed their demands, new kinds of structures to support new habits of life are needed if legacies of social transformation are to be kept alive.

Dome for experimental theater and music, and Lebanese National Pavilion, Oscar Niemeyer, 1975. Photograph by David Burns.

Important parts of this essay evolved as a response to Timothy Mitchell’s keynote address at “Architecture and Representation: The Arab City,” Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, New York, November 21, 2014, included in this volume as “The Capital City” (page 258), and as a result of an ongoing conversation with Nora Akawi, beginning in Palestine on March 20, 2015, on the function and understanding on “the situation.”

Jonathan Littell, Syrian Notebooks: Inside the Homs Uprising, January 16–February 2, 2012 (New York: Verso, 2015).

The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e); Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015), 83.

The exemplary account of this period and its regional effect is Samir Kassir, Being Arab (London: Verso, 2006).

Rudolf Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (New York: Norton, 1971); Heinrich Wolfflin, Classic Art: An Introduction to the Italian Renaissance (1899; New York: Phaidon, 1952); Robin Evans, The Projective Cast: Architecture and Its Three Geometries (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995).

Writing a decade after Evans, Jeffery Kipnis makes the following comment regarding Villa Savoye: “It works for me and on me, but I can understand why others just see a nice looking house.” Jeffery Kipnis, “Re-originating Diagrams,” in Peter Eisenman: Feints, ed. Silvio Cassarà (Milan: Skira, 2006, 194). The comment comes in the context of an attempt to explain the role of the diagram in architecture and its potential political instrumentality. Yet in every example cited in the text, from D. H. Lawrence’s appreciation of Cezanne’s apples to the author’s own appreciation of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, intelligibility is tied to recognition, especially the recognition of signs. As he suggests, “only some are sensitive to architectural effects in the full political dimension” (194). The cultivation of “sensitivity” notwithstanding, and regardless of whether one reads this as a claim for prior acculturation or just personal taste, these signs are always things that are conveyed through formal tropes, in this case Le Corbusier’s Five Points. Architecture may or may not have specificity as a medium, as Kipnis claims, but the model for how the medium works is stubbornly linguistic.

Timothy Mitchell, “The World as Exhibition,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 31, no. 2 (April 1989): 217–36.

Mitchell, “The Capital City.”

12

Territories of Oil

In a paper delivered to the Royal Geographical Society in 1934, Baron John Cadman, chairman of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and the Iraq Petroleum Company, addressed the influence of petroleum on the geography of the Middle East. It was infrastructure, he noted, that was particularly necessary for the exploitation of oil; light railways, telephone and telegraph lines, and pumping stations and pipes for water supply were essential to the uninterrupted flow of petroleum.1 It was an obvious assertion. The same year marked the completion of a 12-inch-diameter export crude pipeline that connected the Kirkuk oil fields, located in the former Ottoman vilayet of Mosul in northern Iraq, to the Mediterranean terminal ports of Tripoli (Lebanon) and Haifa (Palestine). So significant were these pipelines to the new economy in the land of the Tigris and Euphrates that they were referred to as the country’s “third river.” 2

Axonometric drawing of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, Rania Ghosn, 2014. All images by the author.

Yet the third river was only the beginning of the global trade of petroleum across the Middle East. In the aftermath of World War II, a few years after large oil reserves were discovered by American companies in Saudi Arabia, the Trans-Arabian Pipeline (Tapline) was constructed to expand the export capacity of the Saudi concession by carrying crude from wells in the Eastern Province across Jordan and Syria to a Mediterranean port in Lebanon. The Trans-Arabian Pipeline Company was chartered in 1945 by the four American oil companies that held shares in the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) for the sole function of transporting, at cost, part of the crude produced by the sister company. When completed in 1950, the 1,214 kilometer (754 mile) conduit, with a diameter of 30 inches, was the world’s largest oil pipeline system. Conceived to avoid the round-trip tanker voyage around the Arabian Peninsula, as well as the Suez Canal toll, the pipeline was referred to as a “shortcut in steel” and celebrated as an “energy highway.” The company’s publications featured photographs of the infrastructure as a free-floating pipe that merely overlaid the “far and empty” land and vanished into the horizon.3 This image of a “modern trade route of steel” spoke of the infrastructural desire to inscribe a space of oil circulation, or to borrow Manuel Castells’s term, a space of flows, across the Middle East.

Coined by Castells to describe the accelerating conditions of mobility in the global economy, the concept of a “space of flows” captures this intensified exchange of resources, money, information, images, and finance.4 The growth of oil into the largest item in international trade in terms of both value and weight was only made possible by the infrastructure that delivered it from its point of extraction to world markets. Geography, then—or, more accurately, the overcoming of distance—matters greatly. Distance in this respect is not measured in absolute terms but rather as friction of distance, quantified economically as the combined effect of the time and costs imposed by transportation. Given that crude is not worth much at the wellhead, the value of oil requires that it be moved in an efficient and timely manner. Such time-space compression involves a multitude of ways of shrinking distance while accelerating velocity. Geographical theory has examined the extent to which it is possible to overcome the friction of distance by improvements and accelerations in infrastructure within the global space of flows. David Harvey, for instance, argues that the development of communications and transport technologies mitigates the difficulties of capital accumulation by expanding markets and annihilating spatial barriers to profit realization.5

The concept of a space of flows remains insufficient, however, for theorizing the geographical relations that underpin the system of oil. It borrows from developments in biological sciences during the eighteenth and nineteenth century, notably William Harvey’s discovery of blood circulation, to conceptualize the urban process as “flows” of resources through the “arteries and veins” of the geography.6 Reductive metabolic analogies naturalize the politics of circulation and accumulation and cast circulatory systems as the world’s veins and arteries that need to be freed from all possible sources of blockage.7 The flow has no identifiable agency. It eclipses the territorial fixity and silences the negotiations, contradictions, conflicts, and interruptions in the biography of the infrastructure. Favoring a situation of “moving along,” these analogies dismiss friction and violence as the necessary corollaries of circulation. The space of flows is also often used to celebrate the “death of distance” or “end of geography,” but distance and geography are hardly immaterial where oil (and any number of other things in circulation) are concerned.

Why does it matter whether geography is abstracted? The erasure of the geographic abstracts technological systems—their materialities, dimensions, and territorialities. It removes from representation the territorial transformations along the conduit, which the inscription of the infrastructure produces, and overlooks the politics of consensus or dissensus necessary to distribute resources.8 Rather than killing distance and dismissing geography, could we imagine and qualify the spaces of friction within such infrastructural systems? The paramount significance of crude transport within the oil regime could be conceptualized better through the idea of friction within geography. In Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection, Anna Tsing writes that globalization can only be enacted in the sticky materiality of practical encounters, through what she calls “the awkward, unequal, unstable, and creative qualities of interconnection across difference.”9 Tsing suggests that if we imagine the flow as a creek, we would notice not only what the flows are but also the channels that make that movement possible (i.e., the political and social processes that enable or restrict flows). From this perspective, geography is understood as a constitutive dimension of global flows, a tool of government, and a stake of contestation in itself. Space is thus reordered by resource economies rather than eroded by metabolic flows.

Thus, we can reframe the issue of the Arab City through geographies of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline by joining geographical theory and representation to more familiar forms of historical scholarship on energy infrastructure.10 Three friction-vignettes along the conduit reveal the flows and friction of this carbon commodity: these narratives take place in the water troughs, along the Tapline Road, and in the Sidon Terminal buildings. In attending to these places in time, I heed Timothy Mitchell’s call to “closely follow the oil,” which he puts forward in his greatly influential work on oil techno-politics in the Middle East. Closely following the oil means “tracing the connections that were made between pipelines and pumping stations, refineries and shipping routes, road systems and automobile cultures, dollar flows and economic knowledge, weapons experts and militarism”—all of which do not respect the boundaries between the material and the ideal, the political and the cultural, the natural and the social.11 In this framework, one could think of the transnational oil system along the lines of as what Andrew Barry calls a “technical zone,” a set of coordinated but widely dispersed regulations, calculative arrangements, infrastructures, and technical procedures that render certain objects or flows governable.12

With respect to the Tapline corporation and its pipeline project, the inscription of the flow required exploration trips and mappings of alternate routes, international relations and foreign diplomacy relations, private financing, conventions, procurements of rights-of-way, settling of transit fees, and engineering drawings. The construction of such a large engineering project involved resolving labor availability, training, and expertise, as well as conditions of capital and technology. It meant deciding on the movement of local populations, on procurement of pipes and machinery, on whom to employ to construct and operate the pipeline, and how to secure it. Often operating in regions isolated from central power and unconnected to national and regional networks, the transport operation had to “develop” the frontier by deploying roads, ancillary services, and security posts. Simultaneously, the pipeline was built in public relations, in glossy brochures, colorful photos of communities and landscapes, and promises about positive impacts on people along the route. In its multiple dimensions, the fixation of the circulatory system in space produced a territory—simultaneously epistemological and material—through which international oil companies, transit and petro-states, and populations negotiated their political rationalities.

Four maps illustrate the zones at stake in Tapline’s operation. The first represents the Middle East as a space of flows, a continuous background in which state boundaries recede in favor of bold pipelines. The map highlights the desire for a continuous zone of operation in which oil flows in spite of boundaries. However, and as the second map suggests, the continuity of operation did not imply that Tapline would annihilate political borders, for the kingdom’s northern boundary corresponded with that of the Aramco concession. Tapline was a vertically integrated operation, in which the production and transport sectors operated as sister-companies; the flow of oil in the pipeline therefore depended primarily on the perpetuation of the Aramco concession and the reinforcement of Saudi territoriality. For both the concessionary company and the sovereign state, land—or, more precisely, the land’s underground resources—was the new source of value, one that required an enduring order on the surface to secure the subsurface interest.

Map illustrating the Middle East as a zone of oil flows crisscrossed by pipelines.

Map illustrating the zones of control by concessionary companies in Saudi Arabia.

Map illustrating the geography of Saudi Arabian security.

Map illustrating tribal composition of the region.

For Saudi Arabia, the northern boundary represented a double security challenge. The kingdom was keen to guard its northern region against possible external threats from Iraq and Jordan while also reinforcing its rule over the range of Bedouin tribes, particularly those who had seasonally moved back and forth into Iraq in search of water, as shown in the third map. Arabian political boundaries previously had been defined in relation to the territorialities of the tribes, who in turn defined their ranges in relation to access to water. One of the tasks of the Arabian Research Division (AAD), Aramco’s in-house research and analysis organization, was to survey the tribes, their geographies, and their water access. The fourth map speaks of such efforts to depict the tribal zones of influence. It roughly represents the tribal ranges, or diras, for the principal tribes of Saudi Arabia. A dira was not a strictly bounded and exclusively occupied territory but rather a loosely hemmed area of clan control, based around claims to permanent wells. The clear demarcation of the northern boundary was to replace a shifting and negotiated territorial order across northern Arabia. Collectively, the four maps visualize a project of rule with the overlaid territorial claims of the concession, the kingdom, the diras, and the secure border zone.

Tapline thus delineated control in the northern Saudi territory—it inscribed boundaries, settled populations, demanded security, and drove the economy. The Saudi-Tapline Convention exempted the company from an income tax or royalties during its first fifteen years. In exchange, Tapline would pay for “all reasonable and necessary expenses” incurred by the government for protection, administration, customs, health, and municipal works and establish schools and hospitals in the area of the pipeline stations. The company paid a security fee and extended the provision of water and services in the newly established administrative Northern Frontiers Province—originally referred to as the Tapline Governorate. The company drilled fifty-two groundwater wells and provided medical services in its clinics along the right-of-way. It planned the towns adjacent to the pumping stations of Turaif, Rafha, Ar’ar, and Qaisumah; built their public facilities and schools; and supported a home-ownership plan for its employees.

Although the interests along the northern boundary might have been partially shared by the transnational oil corporation and the state, the two were not in consensus over all operations. The space of flow was actually a site through which involved actors negotiated their political rationalities, whether claims for higher transit revenues, labor strikes, or interruptions of flow. Water troughs were a microcosm of the political process. International Tapline officers made available the “hidden natural resource,” local emirs regulated access, and different tribes, no longer confined to their territorial boundaries and water wells, negotiated, sometime violently, for access to water. From its early days of exploration, Aramco made a policy of drilling wells in isolated areas for Bedouins. Water wells drilled for company use were left as public water sources, and Aramco’s annual reports to the government between 1947 and 1960 regularly referred to this program of water development.13 Tapline’s public relations with the Bedu and the governor of the Northern Province were sometimes mediated as “water-shows.” Tapline’s contribution to water development in the northern region was highlighted in company reports and during official visits to the province. For example, during his visit to Turaif, the minister of defense “expressed pleasure at seeing a filled camel trough and complimented the company for looking after the Bedu so well.”14 Through these early encounters, Tapline managers emphasized that they were making “every conscientious effort” on water supply, as outlined in the convention. To get some statistics into the files, aerial photographs were taken of the Bedu area to get a tent census. Also, at the company’s request, the police made a list of all tribes represented, with the names of the headmen and with some guesses as to population, both human and animal.15

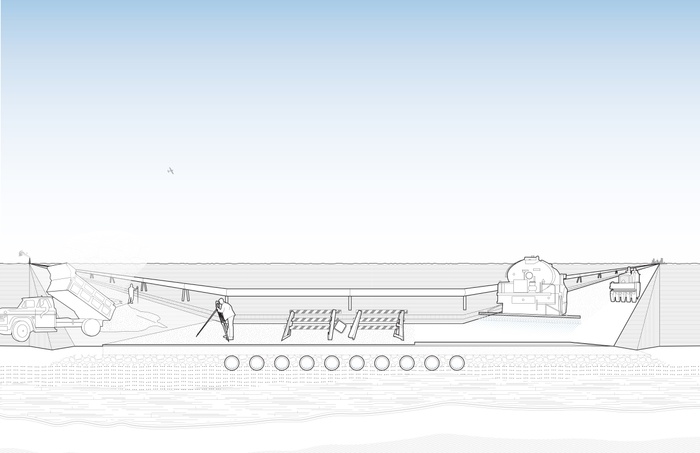

Section drawing illustrating the flow of water into water troughs from Aramco wells.

Tapline had a first taste of the “Bedouin problem” when newly drilled water wells became sites of conflict among the different factions that had come to depend on company wells as permanent water supplies during the summer months. A slowdown in water production, or a change in the wellhead fixtures, resulted in appeals for more water. Formal tribal delegations would report local delays and incidents to Tapline and to the Saudi governor of the province. A 1950 report entitled “Bedouin Survey Rafha” recounts the disputes that occurred when a tribal emir who claimed prior right to the water because Rafha fell within his normal range asked that other Bedouins be stopped from using the water.16 Other tribal factions contended that they had been encouraged by the king to camp near Rafha rather than cross the Iraq border to reach the water of the Euphrates.17 When the emir’s letter to the relations representative at Rafha proved of no avail, he attempted to frighten off the other factions. In the process, the emir of the Northeast Border Force was wounded along with some of his men, and one soldier was killed. Tapline’s representative in Jeddah soon after received a telegram from King Ibn Saud “protesting the incident and alleging that it would not have occurred but for the presence of Tapline operations in the area…that the shooting had occurred as a result of a dispute over water furnished by Tapline in a company trough, and that therefore there was need for a large protective force of Saudi soldiers such as has been advocated by the Government for the past four months.”18 The Tapline representative responding pointed out that such shooting scrapes had characterized the uncontrolled border areas for many years, and he did not think the presence of Tapline was a contributing factor. However, the incident left the representative with the difficulty of planning for the future at Rafha in the presence of multiple factions. It became evident that an “efficient” provision of water required regulation by a local government authority.19

Drawing of grading and paving of Tapline Road, a project funded by the Saudi government as part of a development agreement with Tapline.

A second friction-vignette reveals contradictory interests between the transportation and concession departments of an oil company through the story of the Tapline Road. The convention terms had obligated the Tapline company to construct, maintain, and grade the road along the pipeline at its own expense. During initial construction, an earth road was surfaced with decomposed limestone and marl, and crude oil, rather than asphalt, was used as a binder. The practice continued until the renegotiation of the convention terms in 1963.20 In these negotiations, Aramco was most concerned about the repercussions of Tapline’s choice to capitalize rather than expense the program on its own infrastructural obligations toward the kingdom. Aramco had been expensing its roads on the grounds that once a road was built, the oil company lost control of it and it in effect became public property. Aramco communicated to Tapline its concern that the government’s approval to capitalize the road program set a precedent that Aramco would have to comply with on similar roads, past and future. Also at stake were schools and other community development projects, which Aramco expensed but which the company feared the Saudis might pressure them to capitalize in the future. “Any arguments that we might use for capitalizing the Tapline road can probably be turned against Aramco by the Government… The potential savings to Tapline shareholders by capitalizing the road must be compared with very much larger amounts which Aramco would have to pay the Government if forced to capitalize roads, schools, etc.”21 The road was eventually expensed. In this case, its status as a sister corporation and commitment to the larger financial interest of Aramco influenced Tapline’s decision to meet the kingdom’s developmental requests, despite its initial efforts to limit its commitments to the Saudi government.

Drawing of the Sidon oil spill and the fisherman it affected.

At a regional scale, the political dynamics between Nasser’s pan-Arabism and the pro-Western allies of the Baghdad Pact unfolded around oil spills and labor dynamics in Tapline’s Sidon Terminal, the end station on the Mediterranean, the setting of the third friction-vignette. King Saud’s visit to Lebanon in 1957 symbolically marked the convergence of regional economic interests and American foreign policy. During this visit, John Noble, president of Tapline, welcomed the Saudi king and Lebanese president Camille Chamoun to Sidon Terminal, declaring, “This is an added source of pride to both Tapline and Medreco that they are a means by which the mutual interests of these countries are being served through the transportation of crude oil from Your Majesty’s Kingdom.”22 At the same time, Sidon, home to the terminal, was growing into a stronghold for Nasserite affiliations, particularly with the 1957 parliamentary election of Ma’rouf Saad, a Sidon deputy with socialist labor claims and close ties to the local fishermen. Minor oil spills had begun to pollute the Lebanese coast, attracting the attention of the government, press, and the Sidon labor union under the leadership of Ayoub Shami. Tapline’s management feared a strike and labor unrest in Lebanon: “just as the University of California at Berkeley has its Mario Savio, we have our Ayoub Shami.”23 After a major spill in 1961, the company’s fears were confirmed when a court order sided with local landowners and fishermen affected by the pollution.24 Sidon fishermen contended that chemicals the company used to disperse the oil resulted in damage to aquatic life. The Lebanese government had signed the international treaty protecting a zone extending 100 nautical miles from the coast, within which it was illegal to dispose of oil-contaminated ballast or bilges. While no legislation to support the treaty had been passed, the Lebanese government stressed to Tapline and other countries that the country intended to comply with the treaty. At the same time, in “a gesture of goodwill toward the Sidon community,” the company built two fishermen’s storage buildings in the port area at a cost of about $10,000. During the inauguration ceremony in April 1961—in the presence of Ma’rouf Saad—John Noble called this “philanthropic undertaking by Tapline” a “symbol of the mutual friendship and respect which exists between the community of Sidon and Tapline.”25 The cover of the “Season’s Greetings” issue of Periscope—the company publication—is charmingly illustrated with a color photograph of the Sidon storage facility. Later that year, in another sign of rapprochement with the fishermen, Tapline entered Sidon’s Second Spring Festival with a gigantic fish float adorned with carnations, chrysanthemums, gladioli, and marguerites.26

Throughout the twentieth century, the growth of oil into a global commodity has transformed the Middle East into a hotspot of foreign policy and geopolitical negotiations between producing and transit states, both in peace and war times. Across the region, oil delineates territory through extraction fields, along transportation routes, and at terminal ports. From celebrations of abundance in the postwar Felicia Arabia to the anxieties of the 1973 Arab oil embargo through to the nationalization of oil resources and the Gulf Wars, the subject of oil has all but defined the region in newspapers and policy reports. Yet the profuse literature on oil and the Middle East has mostly addressed the geographies of oil as the exercise of diplomatic power over space. Left out of that narrative are the materialities, scales, and social processes necessary for the establishment and maintenance of oil flows. These three episodes in the life of the Tapline retrace the spatial configurations of such political and economic projects. They narrate how the pipeline has embodied a zone of friction, a zone in which various actors negotiated their overlapping and differing interests.

The Tapline narrative is also relevant to contemporary conversations on energy and infrastructure. At a time when the environment is at the forefront of design concerns, it is imperative that we not bracket out the politics of geography—that its frictions, alliances, and material realities are not ignored when lamenting the “energy crisis” or searching for renewable resources. Many contemporary energy projects continue to be presented as a set of technological artifacts in some faraway, scarcely populated desert. Such images are reminiscent of earlier environmental imaginaries, such as those that inspired the Tapline itself, in which the systemic attributes of the technology remained outside geographic examination. As we transition to new modes of energy, we must examine the geographies of new technological systems; if we fail to do so, we miss any opportunity for political and social transformation. The wind farms, solar fields, and offshore wells that will be our new energy landscape carry their own geographic narratives, their own frictions. It is the role of designers to make those visible.

John Cadman, “Middle East Geography in Relation to Petroleum,” Geographical Journal, vol. 84, no. 3 (1934): 201–12.

Michael Clarke (dir.), The Third River (Iraq Petroleum Company, 1952), 29 min., 16mm film.

Daniel Da Cruz, “The Long Steel Shortcut,” Saudi Aramco World, vol. 15, no. 5 (September 1964): 16–25.

Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1996), 412.

David Harvey, Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2001), 328.

Richard Sennett, Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization (New York: Norton, 1994).

Erik Swyngedouw, “Circulations and Metabolisms: (Hybrid) Natures and (Cyborg) Cities,” Science as Culture, vol. 15, no. 2 (2006): 105–21; Erik Swyngedouw and Maria Kaika, “Fetishizing the Modern City,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 24, no. 2 (2000): 120–38.

See Rania Ghosn, “Where Are the Missing Spaces? The Geography of Some Uncommon Interests,” Perspecta 45 (2012): 109–16.

Anna Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 4.

Much of the discussion here draws from my dissertation: Rania Ghosn, “Geographies of Energy: The Case of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline” (DDes diss., Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2010).

Timothy Mitchell, “Carbon Democracy,” Economy and Society (2009): 399–432, 422.

Andrew Barry, “Technological Zones,” European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 9, no. 2 (2006): 23–53; Gavin Bridge, “Global Production Networks and the Extractive Sector: Governing Resource-Based Development,” Journal of Economic Geography, vol. 8, no. 3 (2008): 389–419.

J. P. Mandaville, “Bedouin Settlement in Saudi Arabia: Its Effect on Company Operations,” report by Arabian Research Unit, December 1965, box 7, folder 15, William E. Mulligan Papers, Georgetown University Library Special Collections Research Center.

Turaif, June 13, 1951, box 6, folder 2, Mulligan Papers.

Turaif, July 25, 1951, box 6, folder 2, Mulligan Papers.

Rafha, July 13, 1950, box 11, folder 21, Mulligan Papers.

“The ‘abdah section consistently claims that Rafha fell within its traditional range… the Aslam and Tuman from the larger section of the Shammar known as Sinjarah took the position that they had been encouraged by the King to camp near Rafha rather than to cross the Iraq border to reach the water of the Euphrates river.” “Camel Trough Troubles,” Rafha, June 18, 1950, box 11, folder 21, Mulligan Papers.

“Shooting Incident May 2 at Rafha Pump Station on Tapline Route,” Foreign Service of the U.S. Rafha weekly report, May 3, 1950, box 11, folder 21, Mulligan Papers.

“Bedouin Survey Rafha,” Rafha, July 13, 1950, box 11, folder 21, Mulligan Papers.

“Schedule of General Specifications Attached to Letter Agreement Dated 24 March 1963 between Government and Tapline,” in “Tapline,” n.d., Al Mashriq, http://almashriq.hiof.no/lebanon/ 300/380/388/tapline/tapline-road/html/ 56.html.

“Pipeline Road,” April 26, 1963, William Chandler personal papers, Boise, Idaho, courtesy of Blaine Chandler and Gail Hawkins.

“King Saud Visits Sidon Terminal,” Pipeline Periscope, vol. 5, no. 7 (November 1957): 1.

“Labor Situation, Lebanon,” December 2, 1966, Chandler papers.

“Oil Pollution of the Sea,” September 20, 1966, Chandler papers; “Oil on the Beaches,” Pipeline Periscope, vol. 16, no. 7 (August 1966): 2.

“Sidon Fishermen Facilities Inaugurated,” Pipeline Periscope, vol. 9, no. 4 (May 1961): 6–7.

“Tapline Float Scores Hit at Sidon Spring Festival,” Pipeline Periscope, vol. 11, no. 6 (July 1963): 2.

20

Interview with Senan Abdelqader

NORA AKAWI

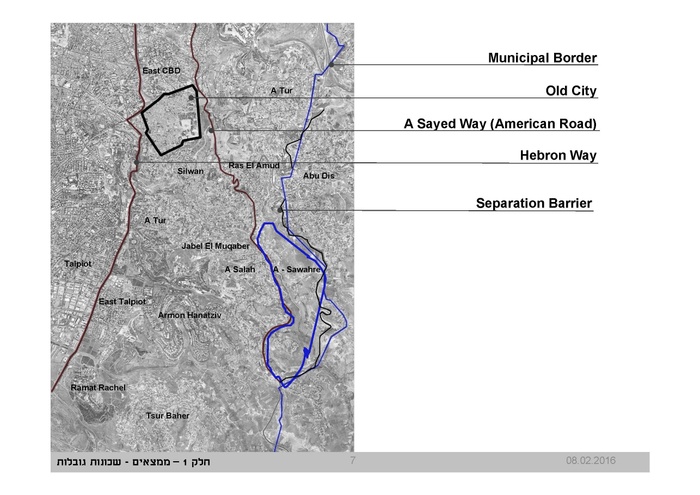

You operate in a context where architecture and planning have been, and continue to be, strategically activated as tools in the occupation of Palestine. Palestinians in Jerusalem continuously face obstacles designed to obstruct their livelihood, with the aim of controlling demographics in favor of a Jewish-Israeli majority. We see this executed through zoning and planning regulations and the construction of infrastructure that fragments Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem and suffocates their foreseen growth, and through systematic home demolitions. You explained that as a result of these obstacles, only 30 percent of the need for housing for Palestinians in Jerusalem is met and that the eastern part of the city was largely developed informally. The urban planning project you did in Arab Al Sawahreh was entirely shaped by this condition. And its outcome, although it can be described as a success, reveals the system set in place by the Israeli authorities to render Palestinian planning in the city impossible. How did your involvement in this project begin?

SENAN ABDELQADER

We started working on this project in 2009. At the time there were many isolated efforts by residents of Arab Al Sawahreh, who were submitting plans to the municipality. They were trying to change the zoning of their lands from nonconstructable areas, to be able to build with permits, and to avoid facing demolition. As you mentioned, one of the many obstacles Palestinians in Jerusalem face is the suffocation of urban growth. This agenda has been clearly introduced into master plans ever since Israel occupied the rest of Palestine in 1967 and annexed East Jerusalem to the Israeli municipality’s jurisdiction. The majority of Palestinian-owned land in East Jerusalem was designated as “open public space area” to make the development of these areas illegal. Since 1967, the population of East Jerusalem grew enormously, especially in Jabal Al Mukabber. People started leaving the denser areas and building in the outskirts of Al Mukabber, in Arab Al Sawahreh.

Of course, many faced the demolition of their homes and other forms of military and legal prevention of construction by Israel. They started working on master plans as a response. The municipality accepted a small number of these projects. But as the municipality officials were receiving more and more of these plans, they resorted to another way of stopping this planned development. They made the pseudo-professional claim that with the growing number of isolated master plans being submitted, a larger plan needed to be put in place for the entire area. Of course we know that when the Jerusalem municipality crafts a condition of this sort for the Palestinian neighborhoods in the city, it’s certainly not with the intention of developing and planning the area, but the contrary. We expect that the goal is to delay the process, to create more obstacles. It’s at this point that I was approached for the project. We had many meetings with the residents and landowners of the area, at first to discuss whether or not we should accept this task at all, with the knowledge of it being part of the Israeli plan to construct yet another hindrance. It wasn’t an easy decision to make. After much discussion we reached a consensus that we should accept the project and develop much-needed plans for this part of Jerusalem, which has never been planned before. It was important to us because it’s the natural extension of the neighborhood Jabal Al Mukabber, south of Silwan, and very close to the Old City. Our main goal was to transform these lands from being labeled as open areas, inaccessible to their Palestinian owners, to lands they can develop and live in, in the heart of Jerusalem.

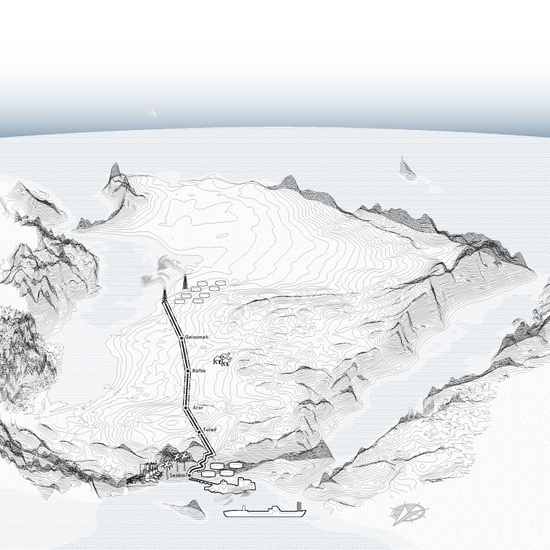

Arab Al Sawahreh site, 2009. All images courtesy of Senan Abdelqader.

NA

You’ve mentioned that the planning process was a collective effort that you led in your office with the landowners, and that this transformed your office space into a platform for civic engagement and participation. Can you elaborate on how this took place?

SA

The most important aspect was that we introduced the landowners into the planning process. Of course, we all knew that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to achieve our goals since the political agenda of Israel in regard to Palestinians in Jerusalem is overtly opposed to these goals. But I explained that our strategy would be to set high aims, and whatever fraction we were able to achieve, we would see as a victory. This was the optimistic beginning of the project, especially as residents were facing obstacles repeatedly and systematically. As I mentioned, before I was introduced into the project, people had already begun isolated planning efforts in order to define their plots and change the designation of their lands from non-constructable to constructable areas. What we aimed for was to bring these efforts together in an urban collective project. One of the interesting challenges was to introduce local modern concepts in order to meet the needs of a highly urbanized society, while at the same time maintaining the social and cultural agreements according to which they had started developing the plans for the area. We developed a housing project in which we considered the social implications of division and subdivision of plots into parcels, and how to organize the buildings, the green spaces, the public spaces, the residential, etc. We developed a plan, an urban imagination, with planning guidelines for the area. That empowered the community to submit more detailed proposals for their lands within a larger collective project. And to do more than ask—to demand—their right to build and develop their lands after having a more complete understanding, from an urban point of view, of what they need and how they want this area to develop: a local modern urban space with public facilities, cultural institutions, and commercial activity. Not only residential.

Community meeting for Arab Al Sawahreh project, 2009.

NA

How did Israeli officials and decisionmakers at the municipality receive your proposal?

SA

At first we were aiming for 7,500 housing units. It was a high-density proposal, but also a direct response to the housing needs for Palestinians in Jerusalem. In 2009, during a key meeting at the municipality that was attended by the city engineer and his deputy, the proposal was immediately dismissed. They asked, “Are you planning on bringing a million Arabs to this area?” In that exact language. This was the beginning of the process. At one point we were being forced to reduce the proposal to 2,500 housing units. We had two options. The first was that we would decide to stop the work entirely and return the situation to the status quo. The second was that we would continue to work with the main purpose of changing the zoning of the area from nonconstructable to allow for construction. At the conclusion of one of our discussions with the landowners and the residents, we decided to proceed on the basis that at least changing the zoning of the land would allow them to build, even if at a lower density than we had initially aimed for. Of course, as soon as land is rezoned from “open,” “public,” or “green” to constructible, its value is raised drastically. But more importantly, as soon as Palestinian landowners in Jerusalem have the possibility to build legally, even if at a lower density, this solidifies the fact that their lands can be developed and solidifies their right to construct and live on those lands.

NA

So did the process play out as you had anticipated? Was it indeed merely another plot for the further hindrance of Palestinian growth in the city?

SA

Absolutely. We have opposed goals. Ours is to secure the infrastructure that would allow Palestinians to remain, live, and grow in Jerusalem, and the Israeli municipality’s goal is to limit this infrastructure to the point of death by suffocation. In the planning process, there were conditions that we were aiming to achieve that we deliberately kept ambiguous—in the ratios between construction percentage, numbers of housing units, and land area. They introduced personnel—arbitrators—whose sole role was to double-check the numbers and do the math three to four times after us. We continued to have meetings on the planning through 2014, and the relationship went from one of suspicion to one of antagonism. At that point they decided that they would accept our proposal not as a master plan, but as guidelines. On the one hand, though collective planning work, in the infamous 2020 plan for Jerusalem, this land in Arab Al Sawahreh was rezoned from open non-constructable to residential, constructible land—on paper. For reasons I mentioned before, this is important as a political planning statement. On the other hand, further conditions were crafted and put in place by the municipality and the District Committee for Planning and Building to make this plan unachievable, impossible to realize. With our proposed plan introduced as the planning guidelines for the area, landowners in Arab Al Sawahreh can now submit master plans for a particular zone in order to complete the approval process for construction. This is where the trickery begins. Master plans covering an area that is smaller than 50–100 dunams [around 12.5–25 acres] are not even considered. Landowners are required to approach the municipality with plans only once they have reached a consensus with all of the owners of at least 50 dunams combined. Consider that the largest ownership of land in that area is 3–4 dunams, and even those are usually shared among a number of family members. They’re being asked to bring ten to twenty families together in order to work on one collective, detailed plan. This is impossible anywhere in the world. This is just one example of how we are forced to work within a system designed to lead to failure, cornered into states of indefinite suspension, working toward plans that are impossible to implement. This is a very frustrating reality, and a destructive condition, representative of the mode of operation and mentality of the occupier.

Arab Al Sawahreh project and surrounding area, Senan Abdelqader Architects, 2009.

NA

During the conference, you explained that the situation in Jerusalem is radically different, even isolated, from other Arab cities: it is under occupation, controlled by a continuous settler-colonial military regime, and as a result the architecture you produce is about existing, surviving, and above all resisting all of the very powerful forces attempting to push you out. You also said that while all of those forces and conditions are designed to limit the local Palestinian aspirations for the city, still you work to bring them a kind of representation through architecture. And in more than once case, your architecture is also representative of repressed and silenced local, collective, Arab, Palestinian aspirations for the city. This is true for the Arab Al Sawahreh planning project, but it’s also true for others like the Mashrabiya House or the sports and cultural center in Beit Safafa. How can you, through design, begin to employ your architecture for criticism?

SA

Shortly after I moved to Beit Safafa, in several informal conversations with friends, neighbors, and members of the community, the need for a cultural and sports center repeatedly came up. We drafted a proposal that was immediately rejected by the municipality on the basis that the residents of Beit Safafa don’t need a center of this sort. For sports facilities, they should use the center in the neighborhood of Sur Baher, six kilometers away. Ten years later, the project was later revived, and we began the design process. We designed a space that would host cultural, educational, and sports activities for the youth of the neighborhood, and conceptually, the project was designed as infrastructure, not as a conventional building. After many revisions, we reached a design proposal that met all of the technical requirements for the project to be approved, but that wasn’t enough. There is a very specific Israeli typology for a sports center, the matnas, that we were expected to replicate. We did use some of the characteristics of this typology, like standard dimensions of particular programs, but we reinterpreted the program and the organization of the various functions to fit our goals for this facility in our particular context. The municipality officials wanted to see an Israeli matnas with the standard two to three stories, standard openings, windows, and doors. We are interested in a local cultural, educational, and sports center for the population of Beit Safafa, one that grows from within, that’s open and acts as infrastructure for the neighborhood. Municipality officials even advised some community members that if they wanted to have a center approved, they should hire a particular Israeli architecture office, which happens to produce a very large percentage of the municipality-approved designs for educational and public sports facilities in the city. The emergence of a local interpretation of an architectural program, with an Arab Palestinian local identity and culture, is threatening to the Israeli bureaucrat.

NA

Although a private project, the Mashrabiya House has also gained local public significance in Beit Safafa. It has become a collective statement and political critique. How did you develop this critique through design?

SA